The Bluebook Change

Hat tip to Eva Resnicow, aka Editrix Lex, who brought this Bluebook change to my attention.

Since the eighteenth edition, The Bluebook has included “(internal quotation marks omitted)” among the parenthetical expressions listed in Rule 5.2. That is The Bluebook rule addressing the broader question of how to signal any number of alterations a writer might make to a quoted passage. Similar parenthetical notices to be appended to citations as appropriate include “(emphasis added)” and “(citations omitted).” Prior to this year’s twentieth edition, The Bluebook itself provided no guidance on when a writer could or should omit internal quotation marks. It merely specified how to report their removal. However, a “Blue Tip” posted to The Bluebook site in 2010 addressed the “when to omit” question. In essence it called for the omission of internal quotation marks whenever the primary quoted material consisted entirely of an embedded quotation. “In all other cases,” the tip advised, “include all internal quotation marks.”

Although less clearly expressed, the twentieth edition has added comparable directions on when to omit internal quotation marks to The Bluebook proper. At the same time, it has removed the “(internal quotation marks omitted)” parenthetical from Rule 5.2’s roster. There is no ban on its use. The phrase has simply been deleted from 5.2, presumably, on the ground that it is unnecessary. Added to 5.2 is a new paragraph (f)(iii) which directs (as Bluebook editions reaching back as far as the fourteenth have advised) that a parenthetical identifying the source of the embedded quote be appended to the citation of the passage in which it appears. Arguably, that identification of underlying source provides adequate notice that the quotation is derivative. The revised rule is also as emphatic as the Blue Tip was before that interior quotation marks should be retained in any case where the embedded quote makes up less than the entirety of the primary quoted passage.

An Illustration of the New Rule’s Effect

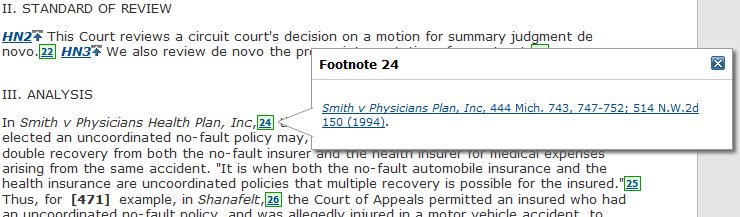

A note published this past June in the Harvard Law Review contains the following passage, footnoted as shown:

Expansive though it is, the President’s enforcement discretion is not limitless. In the OLC’s analysis, legal constraints on nonenforcement derive ultimately from the Take Care Clause24 and are spelled out in a series of judicial opinions following a focal 1985 case, Heckler v. Chaney.25 The Opinion interprets this case law as standing for four general principles: (1) enforcement decisions must reflect “factors which are peculiarly within [agency] expertise”;26 (2) enforcement actions must be “consonant with … the congressional policy underlying the [governing] statutes”;27 (3) the executive cannot “‘consciously and expressly adopt[] a general policy’ that is so extreme as to amount to an abdication of its statutory responsibilities”;28 and (4) “nonenforcement decisions are most comfortably characterized as judicially unreviewable exercises of enforcement discretion when they are made on a case-by-case basis.”29

24. See id. at 4 (locating the President’s enforcement discretion in his constitutional duty to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed” (quoting U.S. Const. art. II, § 3) (internal quotation marks omitted)).

26. The Opinion, supra note 3, at 6 (quoting Chaney, 470 U.S. at 831) (internal quotation marks omitted).

28. Id. at 7 (alteration in original) (quoting Chaney, 470 U.S. at 833 n.4) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Had this note been prepared and published under the twentieth edition, the parentheticals appended to notes 24, 26, and 28 would be gone. Observe that the passage appearing in clause (3) includes internal quotation marks. The marks that the author omitted are those showing that the quotation from the Office of Legal Counsel opinion, to which the “Id.” refers, was itself a direct quote from the Chaney decision. The retained marks appear in the quoted Chaney passage and are attributed in it to a D.C. Circuit opinion. (Bluebook Rule 10.6.2 provides that “only one level of ‘quoting’ or ‘citing’ parentheticals is necessary.” Note 28’s failure to identify the source of the embedded quote is, therefore, in compliance. Also in compliance is the parenthical in note 28 reporting that the alteration to the embedded quote appearing in Chaney originated with the Office of Legal Counsel opinion.)

Courts Quoting Themselves Quoting Themselves

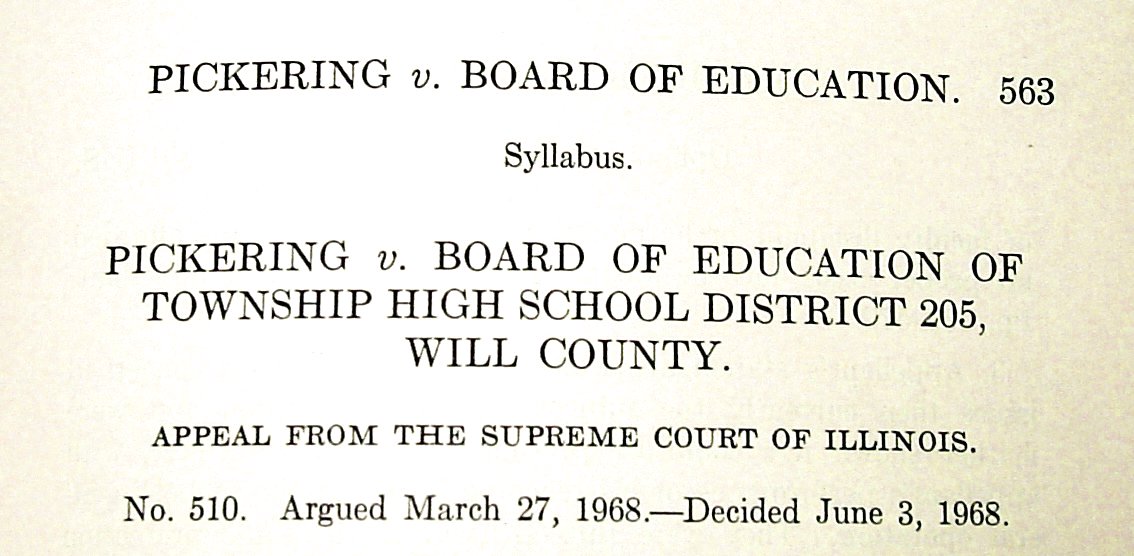

Some courts, including the nation’s highest, remove internal quotation marks under circumstances in which the new Rule 5.2 (and the prior Blue Tip) would require their retention. For example, in Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992) Justice Blackmun’s dissent cites a prior decision of the Court as follows:.

Cf. Los Angeles v. Lyons, 461 U. S. 95, 102 (1983) (“Past wrongs were evidence bearing on whether there is a real and immediate threat of repeated injury”) (internal quotation marks omitted).

Id. at 592.

A portion, but only a portion, of the parenthetical quote (“whether there is a real and immediate threat of repeated injury”) was drawn from a still earlier decision of the Court, O’Shea v. Littleton, 414 U. S. 488 (1974). Per The Bluebook, that quote within a quote should have been wrapped in single quotation marks. However, this is judicial writing, not a journal article. Judges may well consider it far less important to separate out exactly which language quoted from a past opinion of their own court was in turn recycled from a prior one. They are likely, however, The Bluebook notwithstanding, to continue to feel an obligation to note the occurrence of such reuse with an “internal quotation marks omitted” parenthetical.

Courts Quoting Themselves Quoting Other Sources

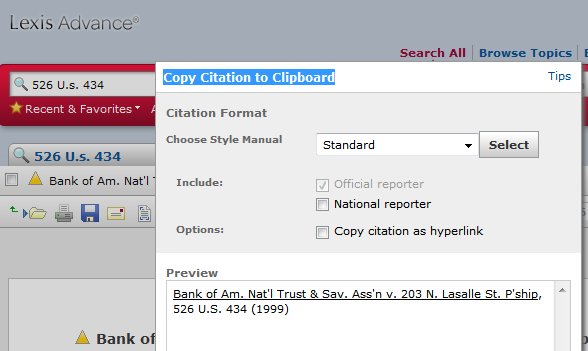

The situation is markedly different when one judicial opinion quotes a prior one that rests on constitutional or statutory language. Being absolutely clear about that dependency argues for retaining the interior quotation marks, even when The Bluebook would trim them. Justice Thomas, dissenting in a 2015 case, Elonis v. U.S., 135 S. Ct. 2001 (2015), wrote:

For instance, in Posters `N’ Things, Ltd. v. United States, 511 U.S. 513 (1994), the Court addressed a conviction for selling drug paraphernalia under a statute forbidding anyone to “‘make use of the services of the Postal Service or other interstate conveyance as part of a scheme to sell drug paraphernalia,'” id., at 516 (quoting 21 U.S.C. § 857(a)(1) (1988 ed.)).

Since Thomas’s quotation from Posters ‘N’ Things consists entirely of language drawn from the U.S. Code, The Bluebook would omit the single quotation marks and rely on the “quoting” parenthetical to inform the reader of the ultimate source.

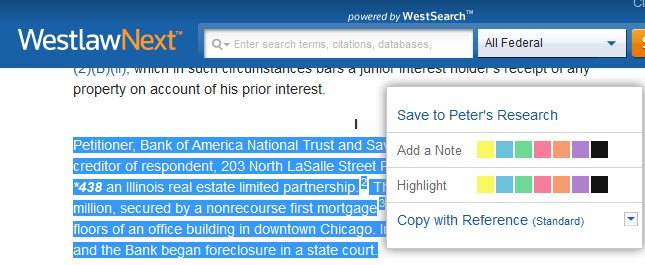

What Should Lawyers Do in Brief or Memorandum?

Negligible space is saved by trimming single quotation marks. Indeed, space is sacrificed and the word count increased if that trimming compels the author to add a four word parenthetical phrase. That suggests, at minimum, lawyers not be influenced by the judicial practice of occasionally removing internal quotation marks from quotes that rest within longer ones, no matter the ultimate source. Absolute clarity argues for including them even when The Bluebook considers them unnecessary. In no case should there be need for an “internal quotation marks omitted” parenthetical.