Court-Applied “Neutral Citation”: A Reform Idea Born When the Internet Was Young

For three decades, appellate courts in a growing number of U.S. jurisdictions have taken advantage of digital technology to distribute their decisions on the Internet in final and complete form, accompanied by all the identification markers that their rules require in later court filings citing one of them. For many, this ended dependence on a single, dominant commercial firm for official caselaw publication, a firm that had, with remarkable success, fought off emerging digital competition through the assertion of copyright in the printed case report volumes it published. (That assertion rested on the volumes’ organization and the company’s editorial additions.) Court-applied case citations promised to be “non-proprietary,” and therefore “vendor-neutral,” as well as “medium-neutral” (i.e., not book-dependent). Official, citable online publication also promised elimination of the, sometimes lengthy, delays produced by rules and norms that called for the identification of judicial opinions and their key passages through use of volume and page numbers drawn from books that were not complete until they contained several months, if not full terms, of judicial output.

Thirty years ago, in 1994, the Supreme Court of Louisiana led the way. The same year Wisconsin’s Supreme Court held a hearing on a similar plan, urged upon it by the state bar, but backed away from implementation in the face of fierce opposition organized by the country’s dominant caselaw publisher. In 1995, the American Association of Law Libraries endorsed a report recommending non-proprietary” case citation and providing detailed guidance on implementation. The ABA promptly added its support, with the endorsement of the U.S. Justice Department. In the years that followed, implementation proceeded, but at a halting pace, across state and federal courts. Moreover, where and when it occurred, that reform took a diversity of shapes. As a result, hopes for a universal or uniform non-print-based, non-proprietary system of U.S. case citation were swiftly dashed. (Citation reform efforts in Canada and Great Britain proved far more successful.)

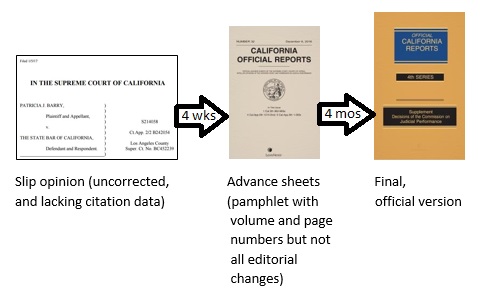

Even where adopted, systems of neutral citation were often compromised. Some state courts that commenced releasing their opinions in digital format, accompanied by non-print identifiers and paragraph numbers, continued to specify that the versions later published in print be considered the final and official ones, warning that they might contain revisions. Many required that case references in court filings contain print-based, volume and page number citations in addition to the court-attached “neutral” identifiers. (During the mid-1990s, significant numbers of lawyers and judges still conducted at least portions of their final caselaw research and analysis in the pages of law report volumes pulled from a library shelf.)

Virtual Case Reports: An Alternative

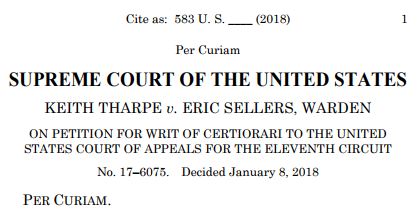

In recent years a less conspicuous model of reform has emerged — the substitution of virtual case report volumes for print ones. For jurisdictions that had retained public control of caselaw publication, rather than ceding that task to a commercial publisher, the plummeting demand for printed case reports posed a serious fiscal challenge. And that challenge often produced lengthy delay. In 2017 Nebraska shifted from seriously tardy print publication to timely electronic release of the Nebraska Reports and Nebraska Appellate Reports. The state’s appellate decisions continue to carry and be cited by volume and page numbers, but from the moment of initial release Nebraska decisions carry the volume numbers and pagination by which they will always be cited. Steps taken since 2021 by the Reporter of Decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court point in the same direction.

Progress as of 2024

The recent changes at the nation’s highest court prompt this review of the uneven success of the thirty-year effort to persuade U.S. courts to publish their decisions electronically, in a non-proprietary, final, official, citable form.

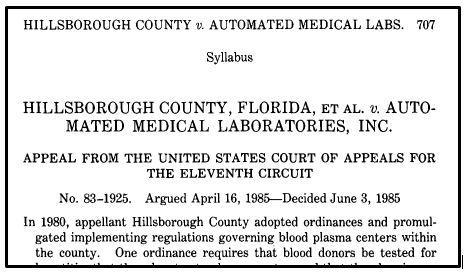

Overall, the view is disappointing. To begin with the lower federal courts, but for one lonely exception neither the U.S. Courts of Appeals nor the U.S. District Courts have budged from their historic reliance on print reports prepared by a single firm, one now owned by the Canadian-based multinational Thomson Reuters. Turning next to the states, the high courts of over half of them (twenty-seven) still specify that the versions of their opinions appearing in proprietary print publications, also published by Thomson Reuters, are the official ones and require citation using their volume and page numbers once attached. In the case of most, Thomson Reuters produces and sells volumes devoted solely to decisions of that one state. For a majority of that group (fourteen states) the decisions in those single-state volumes are simply extracted from the company’s National Reporter System and carry the volume numbers and pagination of the parent, multi-state series. Beyond providing a framework for citation and a traditional component of law office decor, these books themselves see little use. Mainly, they comprise a print archive of texts that nearly all lawyers and judges access online. However, since they constitute the official source of final decision texts and citation parameters for decisions of a majority of state judicial systems, plus the entire federal judiciary below the Supreme Court, firms that compete with Thomson Reuters in the online legal information market must either license data from that company (the case with LEXIS) or buy its books and incur the cost of extracting data from them.

In addition to Nebraska, a few other states have begun publishing their case reports online, compiled into virtual volumes. They include: Colorado, Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and North Carolina. (In Colorado, a recent statute propelled the change.)

North Carolina presents a curious case. In late 2019, the North Carolina Supreme Court adopted a non-proprietary, non-print-based citation scheme, effective at the beginning of 2021. The system was used. Cherry Cmty. Org. v. Sellars, decided in May 2022, was designated 2022-NCSC-62, and its paragraphs were numbered. Later that year, a partisan judicial election (the hot issue being gerrymandered districts) altered the political balance on the court. In January 2023 the earlier order was rescinded, and the court reverted to volume and page citation. Allegedly, paragraph numbering, practiced by the North Dakota Supreme Court for nearly three decades and by over a dozen other state courts for shorter periods, proved too burdensome for North Carolina’s justices and court staff.

Some Models of Reform

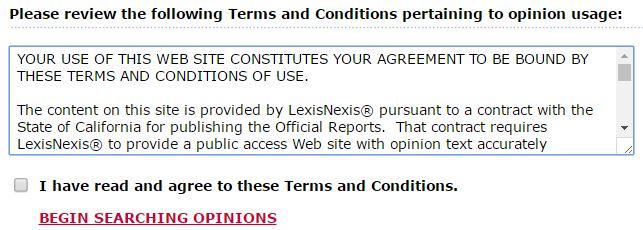

For any jurisdiction considering the provision of direct public access to its case law, there are a range of exemplary models. The Illinois appellate courts, which have employed medium-neutral citation since 2011 and authenticated their online decision texts since 2016, furnish one. Neither court rule nor the Illinois Supreme Court’s own citation practice suggests the need for a parallel citation to the proprietary volumes in which those decisions also appear. As a result, other online legal information services, whether employing conventional search technology or the latest in AI, can offer Illinois decisions, in their full, final, citable form back to the state’s earliest days. (Citable public domain versions of earlier Illinois decisions, as well as those of the other forty-nine states, are available in digital format from Harvard’s Caselaw Access Project.) Two states with medium neutral citation schemes, New Mexico and Oklahoma, have applied those schemes to all past decisions. Each now offers a comprehensive caselaw database for direct public access. Several states that have retained control over the production of official print case law volumes have also established public access sites offering full historic collections. Examples include: Colorado, Nebraska, and North Carolina. The two states with the most lucrative legal information markets, California and New York, continue to secure substantial technical and editorial services under publication contracts that provide public access to a full database of “official” case law, although on terms that effectively block data-harvesting by competing legal information services.

Why Has Progress Been So Slow and Uneven?

For appellate judges and those who serve them, the judiciary’s role as a source of authoritative public legal information can seem far less salient than their responsibility to resolve an unending stream of controversies in the light of all pertinent law. That perspective tends to focus attention on the legal information resources at the court’s disposal, and away from the quality and cost of access to the case law it generates.