1. Truncating and Abbreviating Case Names

The “case name” segment of a case citation serves a very different function from the rest. Rarely is it used to retrieve the decision. Although “case name” searches are possible with all online services, use of the case “cite” delivers more accurate results, particularly if the parties have common names or are frequent litigants. (Try searching on “Smith v. Smith”, “Smith v. Wal-Mart”, or, heaven help you, “Smith v. United States”.)

So why include the parties’ names as part of a citation? I’ve seen a variety of lame explanations (e.g., “reveals the nature of the litigation”), but am convinced that the fundamental justification rests on the brain’s greater capacity to handle names. Imagine having to remember or to discuss cases by their retrieval IDs. Suppose, for example, after making a point in oral argument or law school class you were to be challenged to reconcile your position with “499 U.S. 340.” Those who litigate in federal court may need to think and argue about “Rule 11 sanctions,” but I wager that most will find it easier to refer to the Supreme Court’s 1991 decision published at 499 U.S. 340 using its name or style or title or caption and will be able to remember that name long after forgetting the case cite.

In the official report that decision appears under the heading “Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co., Inc.” In oral exchange, and perhaps in memory, that may reduce to “Feist.” But when constructing a complete citation how should the case name be written? On that question interests of completeness and intelligibility collide with the need to minimize a case citation’s interruption of the flow of argument it is intended to support. As one might expect there are different answers as to how that balance should be struck.

2. Stripping Off Excess

Beginning with the heading or title the deciding court has given a case, there seems to be a fair degree of consensus around several truncation principles:

- If multiple actions are consolidated in an appeal, drop all but the first.

- If multiple parties are involved on either or both sides of the case, use only the first.

- With individuals trim down to a single name, the surname unless that does not appear (“Pickering” rather than “Marvin L. Pickering”, but “Marvin P.” if the surname is not given). This practice can stumble over Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean names when they appear in traditional sequence.

- Shrink longer procedural phrases (in English) to a short set of Latin equivalents (“In the Matter of Buddy Lynn Whittington, Petitioner” becoming “In re Whittington”).

- Limit designations of business organization to the first (which would lop the “Inc.” off “Rural Telephone Service Co., Inc.”).

And so on.

3. Compressing What Is Left through Abbreviation: The Bluebook (and ALWD Citation Manual)

The Bluebook takes an aggressive approach to further party name reduction. It directs that some 144 words that may appear in a business, non-profit, or public entity’s name be abbreviated and prescribes the abbreviation to be used for each. Actually, the number is larger than 144 since some entries are word families – that is two or more words with the same root, treated as one, “Transport” and “Transportation”, for example. Words not on the list may, the manual says, be abbreviated so long as they contain eight letters or more and the abbreviation would save “substantial” space. Any word on the list, however, must “always” be abbreviated “even if the word is the first in a party’s name.” (Rule 10.2.2.) (Prior to 2000 The Bluebook spared the first word, but the seventeenth edition ended that dispensation.) Applying these Bluebook rules to Feist compresses the case name by nearly one-third to Feist Publ’ns, Inc. v. Rural Tel. Serv. Co. The ALWD Citation Manual, which achieves the same result in this and most other cases, contains an even more extensive list of abbreviations. (Striking a very different balance, The University of Chicago Manual of Legal Citation pronounces that “Abbreviations in case names are rarely used.”)

4. The Bluebook’s Limited Influence on This Point

Of the many respects in which the styles prescribed by The Bluebook and the remarkably similar ALWD Citation Manual fail to reflect the diversity of citation formats in the professional writing of lawyers and judges, this may be the most conspicuous. Style manuals governing judicial writing in important states exhibit quite different levels of enthusiasm for case name compaction (shorter lists, a first word exemption). Some add words. Some specify different abbreviations for words on The Bluebook list.

While the rules of appellate practice in a small number of states (Delaware, New Mexico, North Carolina) do appear to direct that case citations in memoranda and briefs conform to the style set forth in The Bluebook, both context and the citation practices of those very courts cast doubt on whether their directives were intended to extend beyond the cite, date, and court components of a case citation to case name abbreviation. Moreover, in several instances (Alabama, California, Idaho) where a court rule refers to Bluebook style, it also authorizes use of one or more alternative citation guides or speaks of The Bluebook as providing guidance (South Carolina). In most U.S. jurisdictions, including the federal courts, there are no directives that can reasonably be construed as requiring the use of The Bluebook’s case name abbreviations. An FAQ at the Supreme Court’s web site states quite explicitly: “The Supreme Court does not have a style manual for advocates before the Court.” It goes on to suggest those seeking guidance might “search Supreme Court materials for citation to a similar document.”

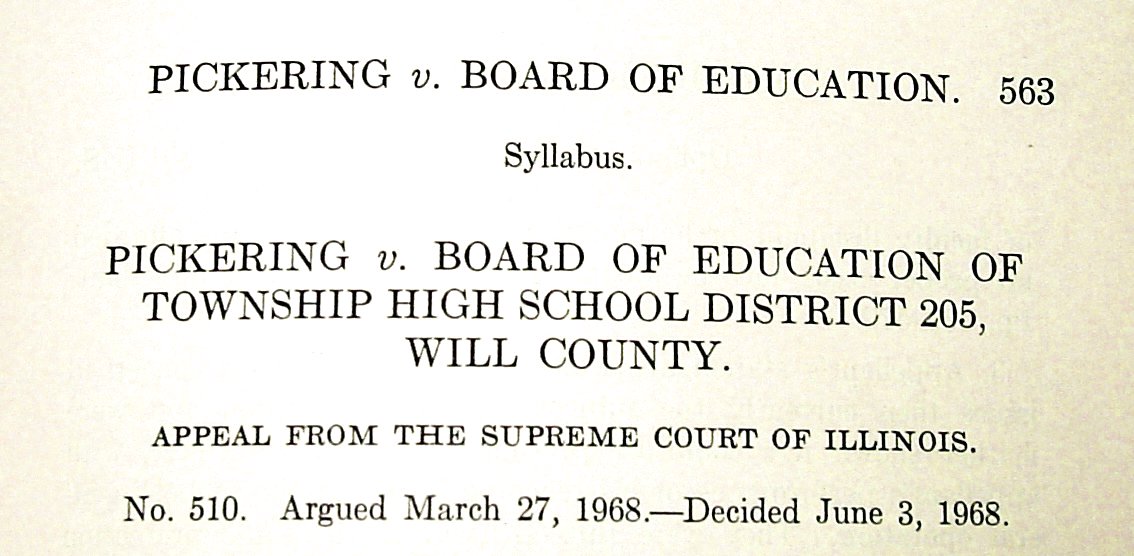

5. The Supreme Court’s Approach

Anyone following that advice will quickly realize that on this point, as on so many others, the Supreme Court’s citations do not conform to The Bluebook. To begin, the Court does not abbreviate the first word of party names. A recent citation of an earlier Supreme Court decision identifies the case as Federal Election Comm’n v. National Conservative Political Action Comm., 470 U.S. 480 (1985). Per The Bluebook both “Federal” and “National” should be abbreviated. Indeed, the length of both “Conservative” and “Political” make them candidates for elective abbreviation. In other respects as well the Court exhibits a gentler approach to abbreviation. There are numerous words on The Bluebook list it does not regularly abbreviate. The Supreme Court’s subsequent citations of “Feist” consistently render its case name, which contains three words on The Bluebook’s mandatory list (“Publications”, “Telephone”, and “Service”), as Feist Publications, Inc. v. Rural Telephone Service Co. A recent citation of Pickering v. Board of Ed. of Township High School Dist. 205, Will Cty., 391 U. S. 563, 568 (1968) abbreviates neither “Township” nor “School” as The Bluebook directs. Even more significantly, the Court’s citation includes both the name of the township and county which The Bluebook would drop. It also employs “Cty.” rather than The Bluebook’s “Cnty.” for “County”. Another case recently cited by the Court is Bank of America Nat. Trust and Sav. Assn. v. 203 North LaSalle Street Partnership, 526 U.S. 434 (1999). According to The Bluebook that case name should be shrunk to Bank of Am. Nat’l Trust & Sav. Ass’n v. 203 N. Lasalle St. P’ship. In short, there is only limited correspondence, in degree or detail, between Supreme Court’s use of abbreviations in citations to its own precedent and The Bluebook rules. Some of the federal circuit and district courts follow the Supreme Court’s lead in this area; many do not.

6. Fifty States, Diverse Styles

A. New York Style

New York’s reporter of decisions has a published style manual. Since the state’s Law Reporting Bureaus oversees the publication of decisions of New York’s intermediate appellate courts and some trial decisions as well that manual guides the writing of judges throughout the state and indirectly influences the citation practices of lawyers submitting memoranda and briefs to them. While the New York manual shares The Bluebook’s enthusiasm for abbreviation, containing an even longer list, it takes a different position on one point of style on which reasonable minds (and therefore citation practices) can easily differ. In forming abbreviations, The Bluebook favors contractions (e.g., “Eng’r” and “Int’l”, though curiously “Envtl.”). Prior to the fourth edition, the competing ALWD Citation Manual used no apostrophes; all its abbreviations ended with periods (e.g., “Engr.” and “Intl.”). Its fourth edition authorizes use of contractions as an alternative (e.g., “Engr.” or “Eng’r”, “Intl.” or “Int’l”). Judging from the advance publicity, the stance of the forthcoming fifth edition is likely to be at least as deferential to The Bluebook on this esthetic matter. But New York courts are not. With only two exceptions New York style ends abbreviations with a period. In New York it is “Assn.” not “Ass’n”, “Commr.” not “Comm’r”, “Govt.” not “Gov’t”, “Intl.” not “Int’l”, and so on.

B. Massachusetts and Illinois

The Massachusetts style manual sides with The Bluebook on contractions. The Illinois manual also agrees that “Association” should be reduced to “Ass’n” but like the University of Chicago manual, it calls for very little abbreviation. Illinois style restricts case name abbreviations to “Association” and ten other words. Even words on this short list are to be written in full if they are “the first word in the name of a party.”

C. Michigan

If New York favors periods, Michigan rejects them as altogether unnecessary. The Michigan Uniform System of Citation includes a number of contractions (e.g., “Ass’n”, “Comm’r”, “Int’l”) but trims the concluding period off all abbreviations. “Brothers” is “Bros”, “Construction”, “Constr”, and so on.

D. Oregon and California

Oregon’s approach to case names rests on the editorial norms of the source. Rather than imposing a set of its own abbreviation rules, the Oregon manual incorporates those of the cited jurisdiction by providing that case names be drawn from the running heads of the case’s official reporter or failing that the regional reporter in which it appears. During the print era this rule, which gives up on uniformity, had the advantage of simplicity. Now that few writers rely on print reporters, with many actually lacking reasonable access to them, the rule’s explicit prohibition on using Westlaw or LEXIS (or presumably any other electronic source) “as a source for the official case name” is manifestly an anachronism. By contrast, the California Style Manual steps into the modern era. Its section 1:1 provides: “Follow exactly the shortened title used in the running head of a paper-based reporter or a shortened title shown in a computer-based source.” (Emphasis added.)

7. What Approach Should the Writer of a Brief or Memo Adopt?

What should an attorney to do in the face of so many different approaches?

A. Be Consistent

First: Be consistent. California has a distinctive style manual. A court rule calls for citations to conform to it or, alternatively, to The Bluebook. It concludes, however: “The same style must be used consistently throughout the document.”

That is a sound principle in any jurisdiction. In states like Illinois, Massachusetts, Michigan, New York, and Oregon where judges follow a clear set of abbreviation norms, but lawyers are not directed to adhere to them, the prudent lawyer employs some set of abbreviation principles consistently. Convenience to the judge may argue for employing the state’s distinctive style, while law school training, available software tools, or the citations provided by the writer’s preferred case law database may point another direction. A failure to adhere to a single, consistent approach throughout a piece of writing is far more likely to create a negative impression of care than a lawyer’s particular choice of style.

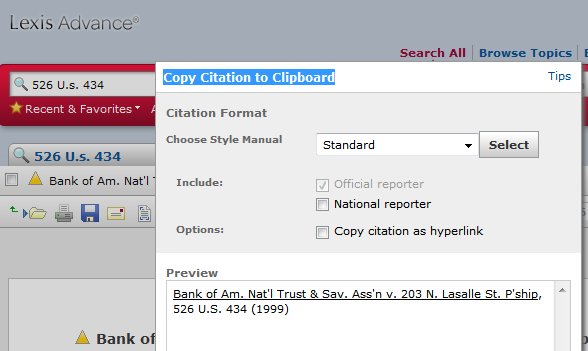

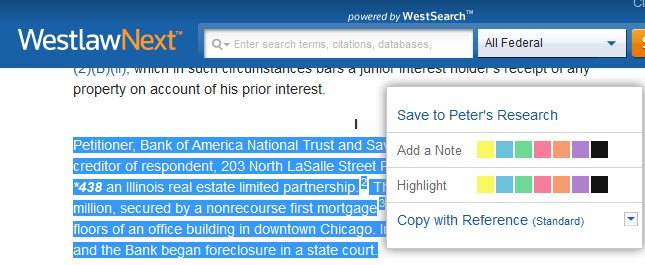

B. Routinize the Process

Second: Avoid devoting serious time to what ought to be routine. Some find it possible to internalize that routine. But consistent use of a single digital source for case law should do most if not all of the job. The major services all impose an acceptable measure of case name uniformity across courts and jurisdictions. Some make it easier than others to copy the complete citation of a retrieved case, including their rendering of its name, but at worst the step requires a simple block and copy of a case’s title or listing. Without marketing the fact, Lexis has long provided case names that conformed to Bluebook citation norms (e.g., Bank of Am. Nat’l Trust & Sav. Ass’n v. 203 N. Lasalle St. P’ship). WestlawClassic conforms to National Reporter System style (e.g., Bank of America Nat. Trust and Sav. Ass’n v. 203 North LaSalle Street Partnership).

WestlawNext and Lexis Advance provide ease of citation extraction as a feature, coupled with a measure of style selection. With WestlawNext the style selected affects how the case name is abbreviated. In both services “Standard” citation format (code name for Bluebook) is the default but not the sole option. Presumably, The Bluebook’s registered trademark prevents their identifying its style using the name by which we all know it.

WestlawNext and Lexis Advance provide ease of citation extraction as a feature, coupled with a measure of style selection. With WestlawNext the style selected affects how the case name is abbreviated. In both services “Standard” citation format (code name for Bluebook) is the default but not the sole option. Presumably, The Bluebook’s registered trademark prevents their identifying its style using the name by which we all know it.

There are also a variety of software tools that offer case name abbreviation along with citation checking and reformatting, but they are a topic large enough to warrant treatment in a later post.

Tags: Bluebook, cases, citation principles