A. A Revived Debate

A recent column by Bryan Garner in the ABA Journal reprised a theme he has advanced for years: Lawyers and judges should stow their citations in footnotes. Placed directly within the text of an opinion or brief, Garner argues, citations interfere with the reader’s ability to follow the writer’s ideas and also with the writer’s use of some of the more important techniques of effective writing. When Garner took his case to the pages of the Court Review in 2001, he focused the argument on judicial opinions, drawing a response from Judge Richard Posner. Posner conceded that the suggestion “had some merit … but not enough to offset its negative features.” Most obvious among these, he wrote, “is that they force the reader to interrupt the reading of the text with glances down to the bottom of the page. They prevent continuous reading.” He also noted that one could tread a middle path: “[T]he author always has the option of putting some … [citations] in footnotes.”

B. How the Electronic Legal Research Environment Bears on the Question for Those Who Write Judicial Opinions

1. Online, the citations in judicial opinions are converted to links

For most of us, the citations to cases, statutes, and administrative regulations we encounter in a judicial opinion are no longer static information about the authorities on which the text rests but electronic pathways enabling immediate access to them. Read from a screen rather than a page they invite the reader, whether on the first pass through or on a subsequent one, to move back and forth between the primary text and the sources it cites. Nor need the exploration end with the first link out, for authorities cited by that initial reference, can themselves be inspected with a touch of the screen or click of the mouse. Cited cases can, with equal ease, be read against subsequent decisions interpreting, distinguishing, disagreeing, or even overruling their position. The routine conversion of judicial citations to electronic pathways out from the text and targets for citator links into opinions has a direct bearing on optimal citation placement or so it seems to me.

2. Treatment of citation footnotes by most legal research services

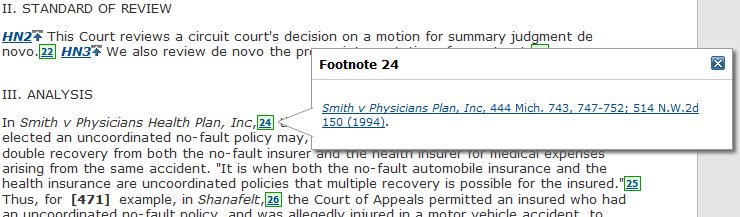

The majority of legal database services convert footnotes to linked endnotes. What this means for citations placed in footnotes can be seen in Google Scholar’s rendition of Harris v. Auto Club Ins. Ass’n, (2013). The route to the authorities cited on a point resulting from this treatment consists of two hops, the first following a link from the footnote call to the note, the second on to the case or statutory provision. Importantly, having been moved from the bottom of the page to the end of the opinion, the citation can no longer be viewed together with the text to which it is attached – a distinct negative.

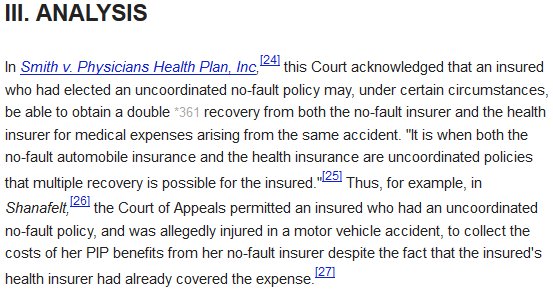

The distance between text and citation is even more troublesome when the citation is itself the target of a citator link or search. Consider a researcher working forward from Smith v. Physicians Health Plan, Inc., 444 Mich. 743 (1994). An up-to-date index of cases citing Smith will list and link to Harris; however, since the full cite to Smith lies in footnote 24 of Harris, the careful researcher will need to go there before backtracking to the paragraph discussing that 1994 decision. And on Google Scholar, Bloomburg Law, Casemaker, Fastcase, and Loislaw footnote 24 has become endnote 24.

The distance between text and citation is even more troublesome when the citation is itself the target of a citator link or search. Consider a researcher working forward from Smith v. Physicians Health Plan, Inc., 444 Mich. 743 (1994). An up-to-date index of cases citing Smith will list and link to Harris; however, since the full cite to Smith lies in footnote 24 of Harris, the careful researcher will need to go there before backtracking to the paragraph discussing that 1994 decision. And on Google Scholar, Bloomburg Law, Casemaker, Fastcase, and Loislaw footnote 24 has become endnote 24.

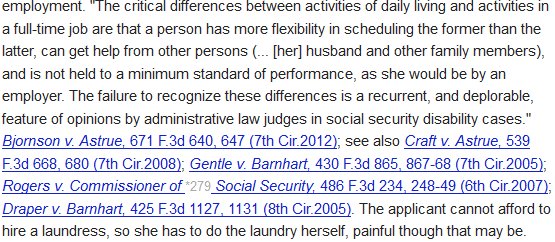

Compare the Harris example with a Posner opinion (or, for that matter, with a decisioin by the U.S. Supreme Court). When I look at Judge Posner’s decision in a recent Social Security case, Hughes v. Astrue, 705 F.3d 276 (7th Cir. 2013) I find the proximity of the citations to the propositions they support a decided help in determining whether and when to follow the electronic paths they offer and a convenience when I make such a journey out and back.

3. The conversion of footnotes to “paragraph notes” or popups

No doubt these considerations explain why neither Lexis nor Westlaw converts judicial opinion footnotes to endnotes. Their “classic” versions place notes directly following the paragraph in which their calls appear (making them “paragraph-notes,” if you will). And their next generation systems, LexisAdvance and Westlaw Next, put footnotes in popup windows that appear immediately adjacent to their calls when activated.

If a judge could be certain that her opinion would be read from the screen and only as transformed by Lexis or Westlaw there would, I think, be a decent argument for placing judicial citations in footnotes. But that is an alternate universe. So long as the majority of caselaw services put greater rather than less distance between footnote calls and their notes than the printed page, inline citations seem the better choice, at least for this reader.

C. How Different Is the Situation for Lawyers Writing Briefs and Memoranda?

While Bryan Garner’s recent essay on citation footnotes draws its examples from court decisions, it takes the same position on the writing that lawyers direct at judges. Garner writes: “whether or not you ascend to the bench someday, you’ll need to make up your own mind on this issue.” In a subsequent post I’ll consider how the efiling of briefs and judges reading from tablets may bear that decision.

Tags: cases, citation principles