I. Introduction

As 2017 opens one U.S. District Court – that for the District of New Hampshire – begins its eighteenth year as an isolated (and incomplete) model of how all federal courts might handle opinion distribution. (Hat tip to Andrew P. Thornton of Little Rock for bringing its record to my attention.)

II. The Simple Steps this One Court Has Taken

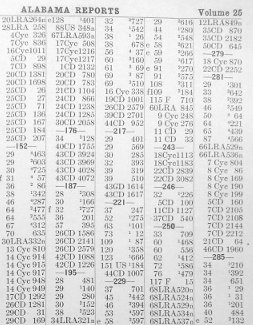

In January 2000, the U.S. District Court in New Hampshire started identifying some of its decisions by year, numbering them sequentially. It designated Silva v. Nat’l Telewire Corp., No. 99-219-JD, decided on January 3, for example, as “Opinion No. 2000 DNH 001“. Panza v. Grappone Cos., No. 99-221-M, decided on October 20 of the same year, is “Opinion No. 2000 DNH 224“. Immediately, upon release, the decision texts, carrying these identifiers, were placed in a court-hosted, searchable database.

The following year the court adopted a local “citation format” rule. That rule directs those citing decisions released after January 1, 2000 and published at the court site to do so “using the four-digit year in which the opinion is issued, the letters ‘DNH,’ [and] the three-digit opinion number located below the docket number on the right side of the case caption ….” For decisions published in “the Federal Supplement, the Federal Rules Service, or the Federal Rules Decisions” the rule authorizes volume and page number citations to those print reporters as an alternative.

This took place well before the E-Government Act of 2002 called upon federal courts to provide web-access to “all written opinions.” While this island of non-print-based citation has escaped the notice of The Bluebook, the 2001 local rule remains in effect and the practice continues. McFadden v. Walmart, 2017 DNH 002, was decided on January 5 of this year. The district’s judges themselves do still, on occasion, cite using opinion numbers. See, e.g., Hersey v. Colvin, 2016 DNH 203, 10 (citing Corson v. Soc. Sec’y Admin., Comm’r, 2013 DNH 144, 24–25). So do attorneys. The New Hampshire Bar Association publishes a monthly “US District Court Decision Listing” that contains summaries of selected decisions of the prior month. The decisions covered are cited by their “medium neutral” or “public domain” opinion numbers.

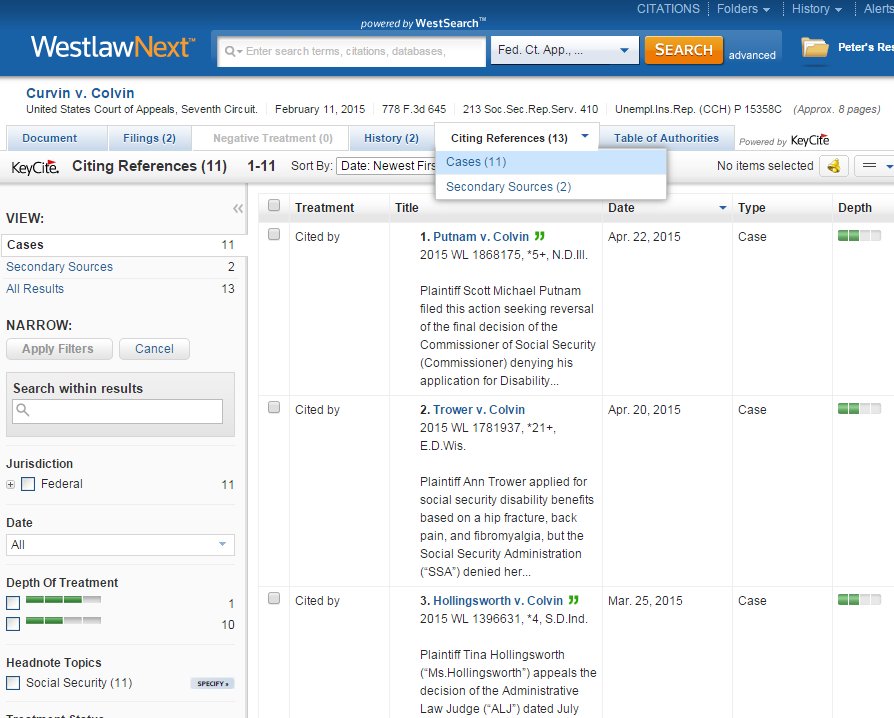

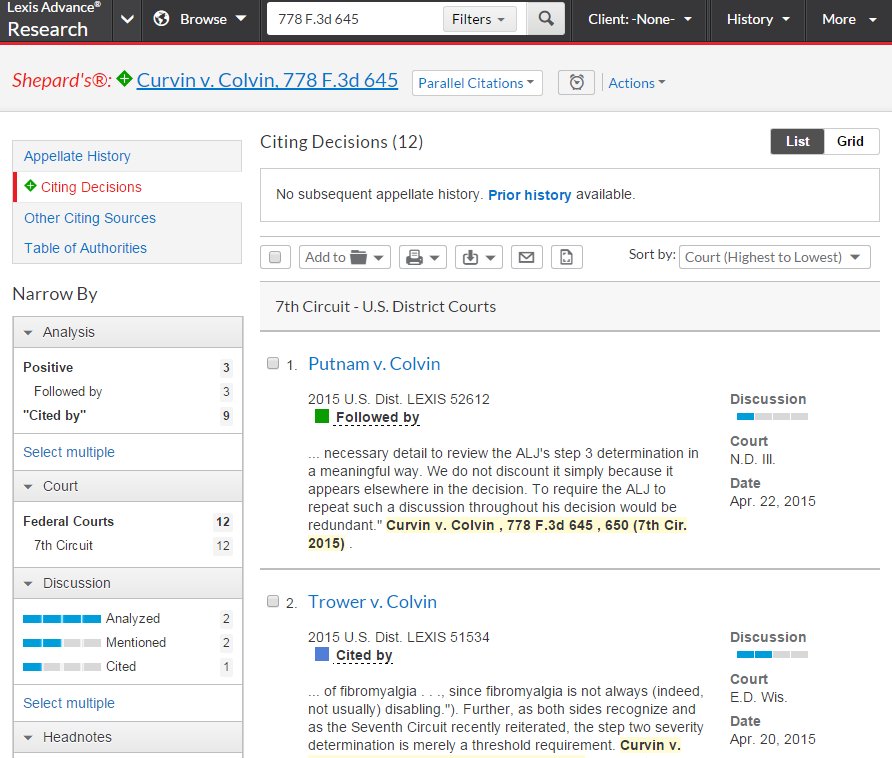

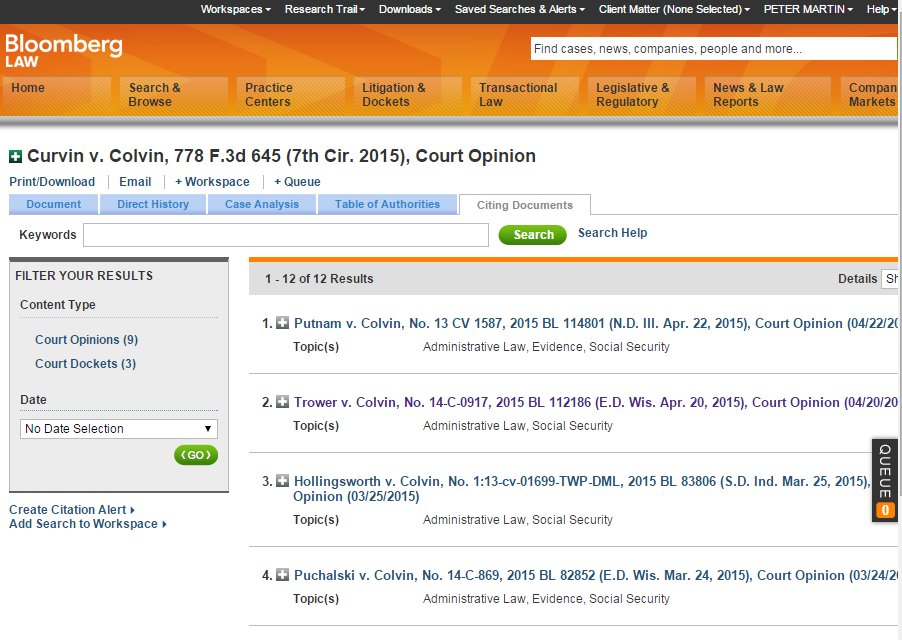

Since the court-attached opinion numbers appear within the texts they identify, researchers need no other citation to retrieve a decision from any electronic source. They do the job on Bloomberg Law, Casetext, Google Scholar, Lexis Advance, Ravel Law, and WestlawNext. They also work with the GPO’s FDsys case law repository (about which more below). For the same reason these sources also provide the opinion number required for a conforming District of New Hampshire citation.

III. Critical Respects in Which the Model Falls Short

A. The Use of Pagination as the Means for Pinpoint Citation

Although nearly all legal research services retain the opinion numbers attached by the U.S. District Court for New Hampshire, only Casetext, Fdsys, and the court’s own database preserve the location of the page breaks in the original version of a decision that the court’s rule directs be used for pinpoint citations. Arkansas and Louisiana, two state systems that, similarly, adopted neutral citation but sought to avoid paragraph numbering by specifying the pagination in a court-released pdf file as the basis for pinpoint references, have suffered the same fate in research services that, like Google Scholar, base their texts for many jurisdictions on the versions published in the Thomson Reuters National Reporter System. Not only are paragraph numbers more precise and more tightly connected to the logical structure of a cited document than pagination, they travel far more reliably with the portions of text they denote into the full range of data services used by those doing legal research.

B. A Failure to Include All Substantive Opinions (Including Magistrates’ Reports and Recommendations)

Not all decisions rendered by District of New Hampshire judges receive court-applied opinion numbers, only selected ones. In compliance with the E-Government Act of 2002 all written opinions of the court, including reports and recommendations by magistrate judges, are made available without charge through the PACER system, where they can be gathered by the online services. A non-trivial number of those opinions – ten percent or more – have not been given opinion numbers nor placed in the court’s searchable database. That is particularly true with categories of cases such as inmate suits and Social Security appeals that are routinely resolved by a magistrate’s report and recommendation, followed by a short judicial order adopting it. As a result, a significant body of district case law cannot be found in the court’s searchable database nor cited by means of opinion numbers. Because of this incompleteness, responsible case law research cannot be carried out using the court’s database. Thoroughness requires use of one of the comprehensive research services. And that leads to citations by the court of its own prior decisions that employ Westlaw or Lexis proprietary cites rather than, or in parallel with, the court’s public domain, medium neutral scheme.

C. Inherent Limits on a Single-District Citation System within a Federal Court with 93 Other Districts

The situation in the District of New Hampshire is categorically different from that in the numerous states that have adopted similar plans of electronic publication and court-applied citation. Matters litigated in state court can often be argued and decided solely on the basis of that state’s own case law. By contrast, rarely if ever can those representing parties to a matter before the U.S. District Court for the District of New Hampshire or the judge handling the case disregard decisions from the First Circuit and other U.S. Courts of Appeals and decisions by other district courts as well. For the district judge that calls for use of one of the two commercial systems available to the federal judiciary; for attorneys, use of those same systems or some comparably comprehensive alternative. The court’s less-than-complete database of decisions may, conceivably, be a useful place to start research but never a place to finish it. Thorough research and consistent citations of relevant decisions lead almost inexorably to the use of one or more of the proprietary systems. With this district’s judges the dominant system is Westlaw. Their pinpoint cites to unpublished decisions, including those in citations to cases that have court-applied opinion numbers, overwhelmingly use Westlaw pagination instead of the page numbers contained in the court’s original version. The citations to Mudge v. Bank of Am., N.A., Gasparik v. Fed. Nat’l Mortg. Ass’n, and Dionne v. Fed. Nat’l Mortg. Ass’n in LaFratta v. Select Portfolio Servicing, Inc., 2017 DNH 007, as released by the court, are examples. LaFratta and other recent decisions reveal a declining use of the court’s opinion numbers and a growing practice of linking citations to authority of all kinds into Westlaw.

IV. The Sorry Fate of Other Single-Court Citation Schemes within the Federal Judiciary

A. The Sixth Circuit’s Ancient DOS-Based Naming Scheme

Since 1994 decisions of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, both published and unpublished, have carried a “file name” identifier. Designed to fit within the name space of the MS-DOS operating system of that era those identifiers consist of eight characters, followed by a period, followed by two more. The file name of one unpublished decision released in January 2016 is “16a0051n.06”. Miller v. Comm’r of Soc. Sec., 811 F.3d 825 (6th Cir. 2016) decided the same month is: “16a0020p.06”. (The “n” and “p” indicate whether the decision is to be published or not.) While Lexis retains these identifiers, they don’t follow opinions into volumes of F.3d or Westlaw. As seems gradually to be happening with the District of New Hampshire opinion numbers, the Sixth Circuit file names have become useless data.

B. The Relatively Brief Run of Neutral Citation in the District of South Dakota

Effective January 1, 1996, the Supreme Court of South Dakota began attaching medium neutral citations and paragraph numbers to its opinions. The practice continues; the court’s rules of appellate procedure still require use of this public domain citation system. Later in that year, by local rule the U.S. District Court for the District of South Dakota laid down the same steps. Even at the time not all of the district’s judges bought into the change. With the appointment of a new chief judge in 1999 who was not an enthusiast, the system continued in the opinions of only one of three active district judges and a magistrate judge. When the district judge in question took senior status in 2008, all trace of the scheme disappeared.

V. Missed Opportunities to Implement Non-Print-Based, Non-Proprietary Citation across the Federal Courts

A. The Judicial Conference Response to the 1996 ABA Resolution

In 1996 the American Bar Association House of Delegates recommended that all U.S. jurisdictions “adopt a system for official citation to case reports that is equally effective for printed case reports and for case reports electronically published.” The resolution proceeded to spell out the key elements of such a system: 1) attachment of identifiers to all decisions, consisting of the year, the court, and a sequential decision number, 2) insertion of paragraph numbers, and 3) adoption of court rules requiring that citations employ these elements. In response the Automation Committee of the Judicial Conference of the United States and the Administrative Office of the Courts simply surveyed federal judges and clerks regarding the ABA citation recommendation. Without asking the Federal Judicial Center for a study or furnishing rationale or context, it simply asked all these individual actors whether they favored the steps. Overwhelmingly they expressed satisfaction with the status quo, hostility to paragraph numbering, and puzzlement over the grounds for change. The recommendation died in committee and has not since been revived.

B. Terms of the E-Government Act’s Mandate

The E-Government Act of 2002, in a section immediately prior to the one addressing the federal courts, directed the creation of and authorized appropriations for an integrated online information system covering all federal administrative agencies. That portal was to be designed to allow public access to agency material “integrated according to function or topic rather than separated according to the boundaries of agency jurisdiction.” In contrast, reflecting the highly decentralized administrative structure of the federal courts, the act’s directive that all federal court opinions be made accessible online was directed at the chief judge or justice of each and every court in the federal system. A more coordinated approach might have drawn attention to the citation issue.

C. Addition of Rule 32.1 to the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

Similarly, the reform movement that led to the addition of Rule 32.1 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure in 2006 might well have focused attention on how the “unpublished” decisions of the U.S. Courts of Appeals, which by the terms of the new rule became citable, could or should be cited. Its sponsor, the Advisory Committee on the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, heard concerns about how those for whom Lexis and Westlaw were beyond reach would access to this large body of case law. Ignoring the citation challenge the committee pointed to the E-Government Act’s mandate as addressing the problem.

The strategic appearance of the West Federal Appendix in 2001, which furnished the means for proprietary volume and page number citation for these “unpublished” decisions to members of the federal judiciary (all of whom have access to Westlaw) almost certainly encouraged this blindness.

D. Implementation of the Federal CM/ECF System, its PACER overlay, and the Fdsys Decision Archive

Federal court electronic case management systems trace all the way back to applications developed by the Federal Judicial Center in the late 1960s. Those established the fundamental structural model that persists to this day: central development of a set of electronic tools, with most decisions about whether, when, or how to use them left to the individual courts. It is probably significant that, having its own administrative and technical support, the U.S. Supreme Court has taken no part in promoting or coordinating technology adoption in the subordinate federal courts. In 1990 Congress catalyzed the opening of existing court-located case and document management systems for remote electronic access. At the time that meant dial-up. The move to electronic filing began in 1995. At around the same time the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts began work on a national party and case number index to the electronic records of the federal courts that had implemented its CM/ECF system. For many federal courts this Public Access to Court Electronic Records service (PACER) subsequently became the mechanism for compliance with the E-Government Act’s mandate. While access to other documents through PACER carries a fee, all documents tagged by the deciding court as “opinions” can be retrieved without charge. However, PACER provides no full-text index of those opinions. They can only be tracked down using docket number, party names, court, and case type.

As filed in a court’s CM/ECF system an opinion is stamped with identifiers that consist solely of case docket number, filing date, and the document’s place in the sequence of filings in the matter – “Case 1:15-cv-00200-LM Document 5 Filed 11/17/15” for example. A uniform federal court citation system could have been appended to this system, either initially or in the “next generation” version now being rolled out. It was not.

In recent years the Government Printing Office Federal Digital System (FDsys) has begun drawing opinions from participating federal courts and loading them into a text-searchable database. Following a pilot phase, the Judicial Conference of the United States authorized national implementation of this inter-branch cooperative venture in September 2012. Over four years later, it remains seriously incomplete in scope; only 49 out of 94 districts courts are included. Furthermore, among included courts, the chronological depth and currency of the data vary considerably. And while GPO authenticates each PDF file it receives from a participating court system and associates a useful array of metadata with it, it has not, as it could, attached an identifier that a lawyer or judge would recognize as a citation. To date, this is simply another more missed opportunity.

At the beginning of 2017, the prospects of a system-wide citation scheme modeled on that launched in New Hampshire at the turn of the century appear dim.

VI. How Should Decisions of the U.S. District Court for the District of New Hampshire Be Cited?

As noted above, this one district court still attaches medium-neutral citations to many, although not all, of its decisions. Whether one obtains such a decision from the court’s database or a commercial source, its opinion number is available and, when included in a citation, it furnishes a highly efficient retrieval identifier. Decisions that have been given a place in F. Supp. or F.R.D. can be retrieved by volume and page number from nearly all research services. Adding the opinion number as a parallel adds negligible value. For “unpublished decisions” whether or not, given an opinion number, Westlaw or Lexis citations may suffice for the court, its judges having access to both. But limiting a citation to one or the other or even both in parallel may leave the opposing party and others who might rely on Google Scholar or Casetext or Ravel without an efficient retrieval hook. Pincites pose a further problem. Lexis includes Westlaw cites for unpublished cases but not Westlaw pagination. Westlaw ignores both Lexis cites and Lexis pagination.

Useful guidance and models come from the court’s own decisions. In Bersaw v. Northland Group Inc., 2015 DNH 050, Judge Joseph LaPlante offered this advice: “[I] would recommend that, with respect to unpublished cases that appear solely on electronic databases such as Westlaw or Lexis, counsel provide as much alternative identifying information (e.g., case number, issuing court, and opinion date) as possible.” The judge, himself, practices what he recommends. A citation appearing in Locke v. Colvin, furnishes a fully fleshed out example of this approach. It reads:

Brindley v. Colvin, No. 14-cv-548-PB, 2016 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10757, 2016 WL 355477, at *5 (D.N.H. Jan. 29, 2016) (quoting Ortiz, 890 F.2d at 528) (remanding where ALJ neither called vocational expert nor explained why reliance upon the Grid was appropriate, but “merely stated, without explanation or citation to record evidence, that [the claimant’s] non-exertional limitations have little or no effect on the occupational base of unskilled light work”) (internal quotation marks and citation to the record omitted).

Four aspects of the example warrant notice:

- While Brindley v. Colvin has an opinion number (2016 DNH 021) it is not included.

- Westlaw pagination rather than pagination from the version held in the court’s database provides the pinpoint reference.

- The addition of docket or case number and full date, as counseled by Judge LaPlante, make it possible to retrieve the Brindley decision from sources that hold it but neither its Westlaw or Lexis citation, including the court’s own database.

- The parenthetical notes provide a clear path to the cited portion of Brindley for any reader who is inspecting that decision on a system in which having the Westlaw star page number is useless.