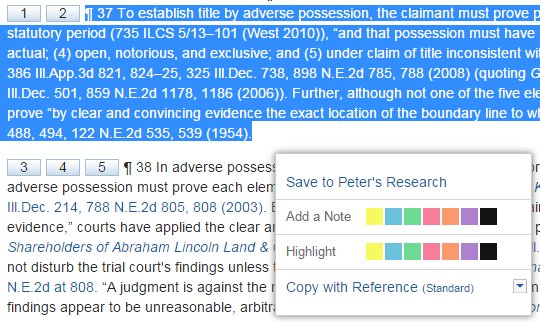

A recent post on the Legal Writing Prof Blog draws attention to Westlaw’s copy-with-reference feature. Its author raises a concern that the option to have citations formatted in the ALWD style still yields citations conformed to that manual’s fourth edition rather than the fifth edition, published earlier this year. Since ALWD’s new version adheres to The Bluebook’s citation style in nearly all particulars, that problem is easily solved: The Westlaw folks need simply to remove the ALWD option. However, those engaged in teaching legal writing and introducing law students to citation need to be attentive to numerous other imperfections in this WestlawNext feature and its LexisAdvance analog, as well as in the citations generated by other research services those 1Ls may employ once in practice.

To begin, although the blogger writes of there being a Bluebook option, that label does not appear among the citation format options of either major service. The default citation style offered by both Westlaw and Lexis is denominated “Standard”. Is that due to trademark concerns? For reasons set out in an earlier post, I doubt it. The truth is that neither system consistently produces Bluebook compliant citations across the several types of authority and to suggest otherwise would be misleading. “Standard” doesn’t make such a claim, although it appears it may lead legal writing teachers and their students, not to speak of lawyers and other online researchers, to believe that is the case.

One other point made in that short post arouses concern. Its author observes that because of this new and amazing feature “I can spend a little less time teaching citation format.” For reasons explained in the latest version of Basic Legal Citation, I view that as a mistake. Let me point out a few reasons why a researcher who wants to employ Bluebook (or ALWD) conforming citations in a brief or memorandum will have to know enough to add, subtract, or modify those delivered by either Westlaw or Lexis.

1. Cases

As pointed out in an earlier post, a major attraction of any copy-with-reference function is that the case name segment of the citations it delivers will have been shrunk through the dropping and abbreviating of certain words. Per The Bluebook a decision rendered in the matter of

Edward Mann and Holly Mann, Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. LaSalle National Bank, as Trustee under Trust Agreement dated March 22, 1960, and known as Trust No. 24184; Ellenora Kelly; John J. Waters; Irene Breen, as Trustee under Provisions of the Trust Agreement dated January 31, 1973, and known as Trust No. 841; Unknown Beneficiaries of Trust Agreement dated January 31, 1973, and known as Trust No. 841; and Unknown Owners, Defendants-Appellants

is reduced to “Mann v. LaSalle Nat’l Bank”. Westlaw’s “Standard” format citation for the case is a close though not identical “Mann v. LaSalle Nat. Bank”. Not The Bluebook’s “Nat’l” nor the “Natl.” favored by earlier editions of the ALWD manual and Bloomberg Law but “Nat.”, the abbreviation long employed by West Publishing Company.

Illinois has its own style manual. It contains a very short list of names that are to be abbreviated in case names. “National” is not one of them. Consequently, citations to Mann by Illinois courts present the case name as “Mann v. LaSalle National Bank”. One might expect that since Westlaw’s copy-with-reference offers an “Illinois” option choosing it would yield that result. It doesn’t; the case name for this decision still comes out as “Mann v. LaSalle Nat. Bank”. LexisAdvance also offers a choice between “Standard” and “Illinois” style citations when copying passages from Mann. As with Westlaw they render the case name identically. But in compliance with The Bluebook, Lexis abbreviates “National” as “Nat’l”.

A big deal? Grounds for choosing Lexis over Westlaw? Hardly. I know of no instance of an attorney being chastised by a court for using non-Bluebook abbreviations and have argued that consistent use of those delivered by the writer’s online source ought to be a totally acceptable approach in professional practice. With their tight attachment to The Bluebook, law journal editors are likely to disagree.

The bigger deal is how Westlaw and Lexis treat the balance of a case citation, particularly if the jurisdiction has, like Illinois, adopted a system of non-print-based citation. Take the recent case of Brandhorst v. Johnson. In decisions of Illinois courts and briefs submitted to them a reference to a particular passage of that case in the form ”Brandhorst v. Johnson, 2014 IL App (4th) 130923, ¶ 57” would be complete. The Bluebook insists that a reference to the National Reporter System (“12 N.E.3d 198, 210” in the case of that passage of Brandhorst) be included in parallel. When the paragraph in question is copied from WestlawNext with its citation in “Standard” format the paragraph number is not included in the cite. (LexisAdvance includes it.) Westlaw does not include the parallel N.E.3d cite in either the “Standard” or “Illinois” style citations for the case. Lexis includes it and adhering to The Bluebook includes a pinpoint page reference. However, Lexis departs from The Bluebook by throwing in the totally unnecessary “382 Ill. Dec. 198, 206” when the “Standard” format is chosen. Westlaw’s “Illinois” style citation for the case adds the parenthetical “(Ill. App. Ct. 4th Dist. June 11, 2014)” which none of the style manuals calls for. The Illinois style guide explicitly states that there is no need for a citation to identify the appellate district “unless that information is of particular relevance to the discussion”. (Moreover, since the district number is part of the jurisdiction’s public domain citation system, with any recent case like Brandhorst its repetition in a parenthetical wastes space.) In sum, neither Westlaw nor Lexis delivers a Bluebook cite for this case. Neither delivers an “Illinois” format citation that conforms to the state’s style guide. Users who would conform their writing to either of those citation standards need to modify or add to what those online systems serve up programmatically along with a copied passage.

2. Statutes (and regulations)

A provision of the Social Security Act with considerable contemporary relevance is to be found in 42 U.S.C. § 416(h)(1)(A)(ii). Copy its language with citation from Westlaw and what you get is “42 U.S.C.A. § 416 (West)”. Lexis renders its citation as “42 USCS § 416”. Neither service is prepared to yield its branded designation of the U.S. Code to the conventionally used generic or official format. Neither includes a date or other indication of the currency of the compilation The Bluebook calls for. And critically, neither provides the absolutely essential subsection and paragraph identifiers that specify the portion of 42 U.S.C. § 416 one is copying. The blocked text may include “(ii)” but that alone is not enough. The same failure to reach below the section level holds with citations to regulations.

3. Conclusion

At their current stage of evolution none of the major research services (including not only Westlaw and Lexis, but Bloomberg Law, Fastcase, and Casemaker) can be relied upon to produce primary law citations that fully comply with The Bluebook or, indeed, any of the other citation styles they may list. In any setting where citation format is critical, users need to know that. And all researchers need to be aware that the citations of statutes or regulations these systems generate will often be seriously incomplete.