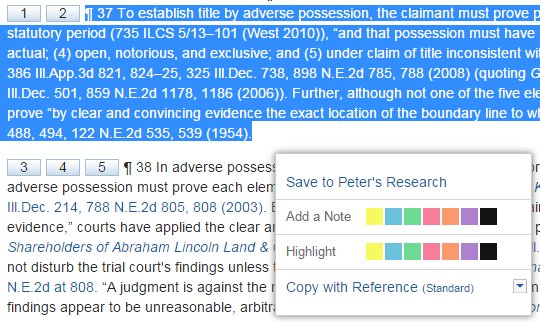

A 2014 review in this blog of the citations delivered by the major online research services along with copied blocks of text concluded:

At their current stage of evolution none of the major research services (including not only Westlaw and Lexis, but Bloomberg Law, Fastcase, and Casemaker) can be relied upon to produce primary law citations that fully comply with The Bluebook or, indeed, any of the other citation styles they may list. In any setting where citation format is critical, users need to know that. And all researchers need to be aware that the citations of statutes or regulations these systems generate will often be seriously incomplete.

Six years on, the gap between promise and performance of the “copy with reference” feature of these systems has not diminished.

Incomplete Citations

Codified Material (Statutes, Regulations, Court Rules) — A Consistent Failure

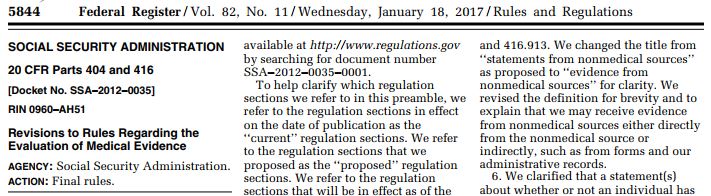

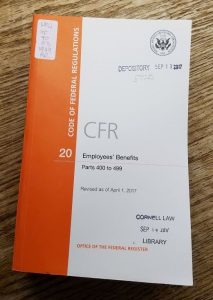

To begin where that prior review ended, citations to highly structured documents like statutes, regulations, and court rules commonly require more than the section or rule number. The copied material may lie deep within a nested framework of numbered or lettered subsections and paragraphs. A full citation to a key passage must specify its exact location within that structure. For examples, consider 42 U.S.C. § 416(h)(1)(B)(i), Ky. Rev. Stat. § 355.4-406 (4)(b), 20 C.F.R. § 404.1520(d), and Fed. R. Civ. P. 19(b)(2). A researcher drawing crucial language of any of those provisions from a non-commercial online source will either copy the entire section or rule or, presumably, know that a copied sentence or two must be accompanied by a full designation reaching all the way down to the subsection, paragraph, or subparagraph level. Copy any of the cited passages alone, from Bloomberg Law, Fastcase, Lexis, or Westlaw and the citation or reference that accompanies it will contain only the section or rule number.

Journal Article References — A Problem on Lexis

In accordance with standard citation practice, a specific passage copied out of a journal article, with reference, from Westlaw will be designated:

Guyora Binder, The Origins of American Felony Murder Rules, 57 Stan. L. Rev. 59, 74 (2004)

The same passage copied from Lexis carries only the following elements:

ARTICLE:The Origins of American Felony Murder Rules, 57 Stan. L. Rev. 59, 74

If the researcher doesn’t want to return, at some later point, to complete her citation to the copied passage, whether in a memorandum, brief, or article, that information must be added to the citation produced by Lexis, manually, at the time the passage is copied.

A researcher on Fastcase and HeinOnline who downloads the pertinent page or the entire article in pdf will receive it covered by a page furnishing the article’s citation in seven different styles including “Bluebook 21st ed.” Since the downloaded file will include the full page on which the passage appears, all the information that will be required for a complete, properly formatted, citation is available.

Bloomberg Law has no law journal database and, therefore, does not pose the problem.

Non-Compliant “Standard” Format Citations

Both Lexis and Westlaw continue to treat citation as a form of branding. The (incomplete) “standard” format citation Lexis furnishes for the U.S. Code provision listed above is “42 U.S.C.S. § 416 (LexisNexis, Lexis Advance through Public Law 116-163, approved October 2, 2020)” while Westlaw delivers “42 U.S.C.A. § 416 (West).” In jurisdictions where these two companies compete in print, their respective citations to state statutes exhibit the same tendency. On Lexis, even the federal rules receive this treatment: “USCS Fed Rules Civ Proc R 19” instead of “Fed. R. Civ. P. 19.” Unlike the failure to furnish a complete designation for a copied passage, this proprietary flavor of a “standard” format can be rectified in a final piece of writing through use of a “search and replace” that converts all statutory, regulation, and rule citations to their official or generic form.

The same is true of non-compliant case name abbreviations. The “standard” format case references of both Lexis and Westlaw, as well as the citations delivered for cases by Bloomberg Law and Fastcase deviate in some particulars from the abbreviations set out in The Bluebook. (20th ed.). (To date, none have moved to the additional and altered abbreviations of the latest edition.) For example, Westlaw favors the abbreviation “Nat.” over The Bluebook‘s “Nat’l” for “National,” Lexis follows The Bluebook, Bloomberg Law reduces “National” to “Natl.” and Fastcase leaves the word in full. Both Lexis and Westlaw followed The Bluebook‘s 2015 switch from “Adver.” to “Advert.” as the abbreviation for “Advertising” and from “Cnty.” to “Cty.” for “County.” Bloomberg Law did not; Fastcase abbreviates neither word.

The good news is that all four systems appear quite consistent in their treatment of case names. As a consequence, to the extent that close Bluebook adherence is important to a writer who has relied consistently on any one of them, a “search and replace” operation can address discrepancies. For most purposes, that consistency itself is sufficient. The California Style Manual explicitly authorizes use of “a shortened title shown in a computer-based source” for cases.

Jurisdiction-Specific Citation Formats Generated by Lexis and Westlaw

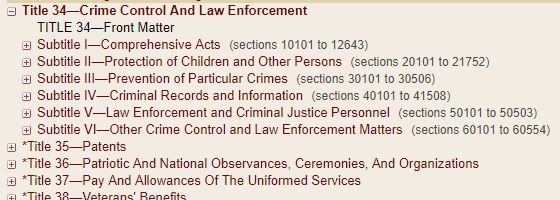

Lexis and Westlaw invite the user to select among an array of formats for the citation attached to a copied passage. The format choices offered by Lexis include “Standard,” “ALWD,” and all fifty states. Westlaw’s list adds a “Westlaw” format option, but includes only 34 states plus the District of Columbia. (Omitted are smaller states in which Thomson Reuters does not sell a West-branded statutory compilation in print.)

Westlaw’s omission of states like Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas is particularly troubling since they (and numerou others) have quite distinctive local ways of citing their own codified statutes and regulations. See Basic Legal Citation § 3-300. Within Alaska, for example, a provision for which The Bluebook prescribes citation in the form “Alaska Stat. § 28.22.011 (<year>)” will be cited “AS § 28.22.011.” Choosing the “Alaska” format on Lexis gets that result, albeit with a brand and date element appended “(Lexis Advance through 2020 SLA, ch 32).” Overall, Lexis does a better job of furnishing state-specific versions of citations to statutory and regulatory codes.

In jurisdictions where there is an official report, Lexis gives the user a choice as to whether to attach it to a copied case reference, whether to include a citation the Thomson Reuters regional reporter, or whether to provide both. Citing an Illinois case to an Illinois court, one need not include any parallel citation. The medium neutral, public domain citation, by itself, is complete — “Yarbrough v. Nw. Mem’l Hosp., 2017 IL 121367, ¶¶ 21-22.” Lexis will produce Illinois citations in that format. In contrast, Westlaw gives the user no choice over whether a reference will include the company’s parallel regional reporter citations. Its Illinois version of the same reference (containing four unnecessary words) is: “Yarbrough v. Nw. Mem’l Hosp., 2017 IL 121367, ¶¶ 21-22, 104 N.E.3d 445, 448–49.”

In Conclusion

As of 2020, none of the “copy with reference” features of the major online legal research services can be relied on to provide complete, pinpoint citations of the principal categories of primary legal authority, in either fully compliant “standard” or jurisdiction-specific format. While they are, unquestionably, a convenience, they do not remove the need for a user to have full command of the requirements of legal citation.