The twenty-first edition of The Bluebook has eliminated the separate table that previously prescribed how to abbreviate common words appearing in the name of a cited publication. That table, Table T13.2, was a single purpose reference, to be used solely when citing articles. Its columns, together with the institutional abbreviations contained in Table T13.1, turned “Harvard Law Review” into “Harv. L. Rev.”, “Yale Law Journal” into “Yale L.J.”, and “Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization” into “J.L. Econ. & Org.” A writer consulted Table T6, not T13.2, when abbreviating a word in a case name or in the name of an institutional author. In this latest edition, The Bluebook has collapsed the two. The new, consolidated, T6 applies to case names, and to the names of publications, as well.

Modest Gains

For the sponsoring organizations this constitutes the type of periodic revision valued by all publishers of higher education texts. It is the sort of change that will, inevitably, undercut the market for second-hand copies of The Bluebook‘s prior edition among the nation’s annual 38,000 or so beginning law students. For users the merger achieves only a slight reduction in the book’s heft—two pages, plus or minus. Any additional gains for a novice user of the reference, one of those beginning law students, say, are less clear. For legal professionals committed to Bluebook compliance, as well as the research services and citation software tools upon which they rely, the change raises confounding issues.

Significant Costs

Unnecessary and Confusing Case Name Abbreviations

Providing separate tables for distinct types of material poses little risk of confusion, allows them to be tailored to the word patterns characteristic of each type, and relies on an abbreviation’s context to assist the reader. (The Bluebook continues to employ many special purpose tables—one for court names, another for legislative documents, etc.) Set against uncertain gains, the merger of T13.2 and T6 has definite costs. Collapsing the two deploys abbreviations that worked well so long as it was clear that they were part of a publication title into a setting in which they are far more likely to confuse. The word “Law,” ubiquitous in journal names, illustrates the poor fit. “Law” was never a candidate for a case name abbreviation. Party names contain many more, much longer, “L” words. In the new T6 “Law” has two entries and accompanying instructions on when to use each. “Journal” at seven letters was not abbreviated in prior versions of T6, but as part of a periodical name the single letter “J” served as an intelligible stand-in. Had “Journal” been included in the pre-merger T6 it would most likely have been trimmed to “Jour.” (The only single letter abbreviations contained in that T6 were for the four cardinal directions. Consistency with reporter abbreviations in Table T1 would have rendered “Atlantic” as “A.” but it is, and continues to be, shrunk only to “Atl.” when part of a case name,) Consider a 2018 decision of the Nevada Supreme Court. Per The Bluebook’s twentieth edition, the case should be cited as: “Clark Cty. Sch. Dist. v. Las Vegas Review-Journal, 429 P.3d 313 (Nev. 2018).” Run through the new consolidated Table T6 its name becomes: “Clark Cty. Sch. Dist. v. Las Vegas Rev.-J.”

Only “University” has been spared merged treatment. The T6 instructions conclude with a paragraph that applies solely to periodical titles. It directs that although the abbreviation for “University” in T6 remains “Univ.” when that word is part of a journal name it can (and should) be reduced to “U.”

The Inclusion of Abbreviations for Words that Infrequently Appear in Case Names

Any number of the words moved from Table T13 into Table T6 have fewer than eight letters. Many of those appear rarely, if ever, in case names. Examples include: Africa, Ancestry, British, Civil, Cosmetic, Digest, Dispute, English, Faculty, Forum, Human, Injury, Labor, Lawyer, Library, Military, Mineral, Modern, Patent, Policy, Privacy, Record, Referee, Statistic, Studies, Survey, Tribune, Week, and Weekly. Inserted into a table used to abbreviate case names, words like these constitute unnecessary clutter. Their prior placement in Table T13 alongside the Institutional name abbreviations with which they often must be combined (abbreviations which remain in T13) provided the writer doing a lookup or format check on a journal citation, a simpler path.

Displacement of Established and Intuitive Case Name Abbreviations

The merger also forced, otherwise unnecessary, changes in a number of case name abbreviations. Separate tables allowed different abbreviations for the same word, with context determining which to use. The universe of journal names is many multiples smaller than that of party names. In a citation they stand next to the full, unabbreviated title of the cited article and the author’s name. This warrants a very different trade-off between the saving of space and clarity of reference. That is why abbreviating “Law” as “L.” and “Journal” as “J.” and “Review” as “Rev.”—in the context of a journal name—works, while abbreviating a litigant named “Los Vegas Review-Journal” as “Los Vegas Rev.-J.” seems both unnecessary and cumbersome. That is why abbreviating “Employ,” “Employee,” and “Employment” as “Emp.” worked in a separate table for journal titles, but erasing the distinctions among “Employee” and “Employer” and “Employment,” as the merged T6 does, reduces clarity. One can readily read and refer to “White v. Mass. Council of Constr. Emplrs, 460 U.S. 204 (1983)” (abbreviated according to prior editions of The Bluebook) by name, while “White v. Mass. Council of Constr. Emps., 460 U.S. 204 (1983)” (abbreviated per the twenty-first edition) leaves a reader unsure, without checking, whether it is the “Massachusetts Council of Construction Employers” or the “Massachusetts Council of Construction Employees.” Previously, the abbreviation “Lab.” stood for “Laboratory” in a case name, “Labor” when it appeared in a journal title. In context both were clear and not a source of confusion. The table merger forced disambiguation. “Laboratory” became a totally non-intuitive and unfamiliar “Lab’y”. Grotesquely, under the general rules on plurals that results in an abbreviation for “Laboratories” of “Lab’ys” (already, the subject of justifiable ridicule).

Will the Change Alter Professional Citation Practice?

To what degree will such changes in Bluebook abbreviations affect professional, as distinguished from academic, writing? The answer is unclear. It depends, in large part, on how the online research services and electronic legal citation formatting tools respond. Case name abbreviations remain a matter of significant jurisdictional variation. For certain, the U.S. Supreme Court will continue to cite its 1983 White decision by the name “White v. Massachusetts Council of Constr. Employers, Inc.” Illinois appellate courts citing it will not even abbreviate “Construction.”

In part because of this degree of jurisdictional variation, the two dominant legal data vendors offer “choice of format” in their copy-with-citation features. Among the choices both offer for cases is one labelled “standard.”

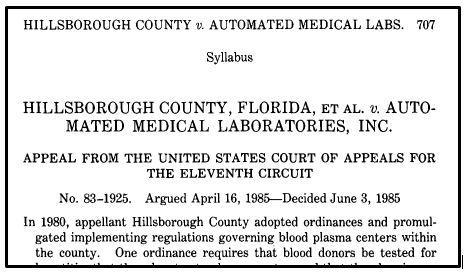

Currently, both LEXIS and Westlaw provide a “standard” format case name for this 1985 decision of the U.S. Supreme Court at 471 U.S. 707 of: “Hillsborough Cty. v. Automated Med. Labs., Inc.” Will they, should they convert “Labs.” to “Lab’ys”? Will they, should they retrospectively convert all the case names they deliver as part of a “standard” citation to the word abbreviations brought into T6 from T13.2 or altered there because of the merger? When the twentieth edition of The Bluebook arbitrarily altered the abbreviation for “Advertising” from “Adver.” to “Advert.” and the abbreviation for “County” from “Cnty.” to “Cty.“ in 2015, LEXIS and Westlaw followed. Bloomberg Law did not. “Adver.” still regularly appears in appellate brief citations.

As yet, none of the online research systems have incorporated the numerous new abbreviations resulting from The Bluebook’s 2020 table merger. Will they? May they not, instead, decide that the abbreviations resulting from this ill-considered move don’t warrant the label “standard,” since they fail to conform to widespread professional practice? An option they might consider is the addition of a new “law journal” format to their array of options, thereby meeting the need of those law student editors and academic writers for whom Bluebook conformity is essential. A similar puzzle over audience or market confronts those numerous other enterprises that provide legal citation formatting tools and citation guides.