I. Introduction

Alone among California’s branches of government, the state’s appellate courts remain stuck in a pattern of legal publication designed around books. Other states now furnish unrestricted digital access to final, official, citable versions of their judicial precedent. California does not. The current “official reports” publication contract with LexisNexis runs until June 2017. At that point the state’s judicial branch could do the same. There are compelling reasons why it should.

II. The Constitutional, Statutory, and Contractual Framework

Every year California’s appellate courts hand down roughly one thousand decisions that count as legal precedent. Those opinions, containing interpretations of constitutions (federal and state), statutes, and regulations, as well as rulings on points of uncodified law, are binding on the courts, governmental agencies, businesses, and citizens of the state. To a degree true of no other state’s jurisprudence they also influence decisions of the nation’s other courts.

Recognizing the critical importance of public access to this body of law, Article VI, Section 14 of the California Constitution states:

The Legislature shall provide for the prompt publication of such opinions of the Supreme Court and courts of appeal as the Supreme Court deems appropriate, and those opinions shall be available for publication by any person.

California’s legislature has discharged that constitutional mandate by establishing the position of “reporter of decisions.” Section 68900 of the California Government Code directs the Supreme Court to appoint such an official and prescribe his or her duties. Adjacent sections require publication of the official reports under the supervision of the Supreme Court, those reports to contain “[s]uch opinions of the Supreme Court, of the courts of appeal, and of the appellate divisions of the superior courts as the Supreme Court may deem expedient” and to be accomplished through a contract of two to seven years duration.

The current contract ends in June 2017. It has been extended to the full 7 years allowed by statute. In anticipation of the next contract, the state’s new reporter of decisions, Lawrence Striley, must begin work with the principal stakeholders to craft a framework for the request for proposals (RFP) to be issued soon. (By statute the contract is “entered into on behalf of the state by the Chief Justice of California, the Secretary of State, the Attorney General, the President of the State Bar, and the Reporter of Decisions.” Cal. Gov’t Code § 68903.) For important reasons that framework ought to be quite different from the one embodied in the 2010 RFP. Time is ripe for a fundamental change in how this important public function is carried out.

III. A Vast Discrepancy between California’s Current Official Reports Model and How Case Law Is Disseminated and Researched in 2017

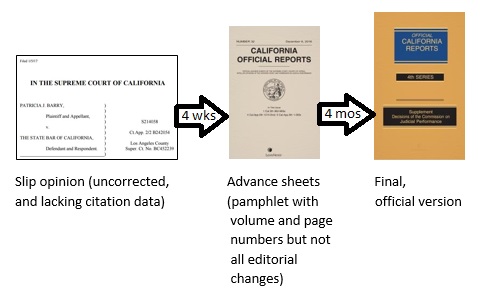

During the era of print law reports, judicial opinions made their way slowly to their final archival form – a bound volume containing large numbers of them. Precedential decisions were first released as “slip opinions,” which had only limited circulation beyond the parties. Following initial release, a reporter of decisions and staff subjected all “slip opinions” destined for publication to thorough editorial review. This post-release editorial work, conducted under court oversight, included the addition of parallel citations, the checking of quotations and citations for accuracy and proper format, careful proofreading and copy editing of decision texts. During this period the reporter’s office also added summaries, headnotes, and headings to individual decisions as well as the indices and other finding aids that organized the contents of completed volumes. These substantial editorial duties required time. However, so long as nearly all effective distribution of decisions took place in print, delay was a natural part of the process. Decisions first had to collect in sufficient numbers to be issued in a temporary paperbound volume. Only upon their release in that “advance pamphlet” form could they carry the volume and page numbers by which they would henceforth be cited and their future influence tracked by means of a citator. Most of the reporter’s editorial work on decisions took place in the month or months prior to “advance sheet” distribution, but the subsequent accumulation of the pages needed to fill a bound volume provided additional time for further editorial correction and revision. In California that print-based work flow still prevails and is embodied in the official reports contract. It takes over a month for a decision of the California Supreme Court to acquire the volume and page numbers by which it and its key passages will need to be cited, together with the accompanying editorial revisions and corrections contained in its “advance pamphlet” publication. The bound volumes that follow accumulate a full four months of opinions.

Yet the print volumes, nominally the subject of the current official reports contract, no longer provide the principal pathway to the state’s precedent. From start to finish, the vast majority of lawyers, judges, other public officials, and members of the general public doing case law research turn to electronic sources. Each year fewer and fewer libraries buy the bound volumes that hold the final and official text of California’s appellate courts.

A second and related change has taken place. During the prior century those who wished to do California case law research had a choice between two competing sources: 1) the official reports produced under supervision of the reporter of decisions; and 2) a set of commercial reports derived from them sold by the West Publishing Company. Where once there were two, there are now many. The digitization of law has been accompanied by a proliferation of case law research offerings. The “official reports” service maintained by the holder of the current contract (LexisNexis) competes with Westlaw, Bloomberg Law, Casemaker, and Fastcase, plus a spectrum of free services led by Google Scholar.

Recent start-ups, most of them based in California, continue to add to the list.

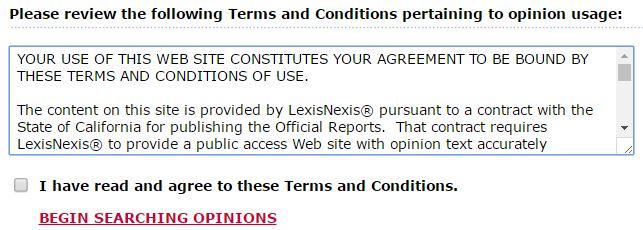

According to the most recent ABA Legal Technology Survey, LexisNexis is principally relied upon by fewer than one in three U.S. lawyers. A direct consequence of that limited reach is that the contracted for summaries, headnotes, and headings added to California decisions under the supervision of the reporter’s office are not seen, let alone used, by most researchers of California law. A further and more disturbing consequence is that the final, citable versions of decisions produced under the current publication contract are not “prompt[ly] … available for publication by any person.” Concededly, the Judicial Branch website does provide prompt access to the original “slip opinions,” but these lack the editorial revisions that occur later during the publication process and also, of at least equal importance, they lack the volume and page numbers by which specific holdings of those cases must be cited in any subsequent legal proceeding. While the LexisNexis contract requires publication of the official reports in electronic form, it does so on terms that preclude their being a data source for publication by others. The same is true of the “California Official Reports Public Access Web site” maintained by LexisNexis for the Judicial Branch. Users are instructed that the site is for personal and not commercial use.

Moreover, the decisions it offers have been stripped of the pagination that any professional user or other publisher would require.

In sum, any firm other than the holder of the present official reports contract, must choose between a pair of unsatisfactory approaches:

- offering preliminary “slip opinion” versions, while obtaining and inserting volume and page numbers in them drawn from the official print edition once available or

- re-digitizing the final print versions in their entirety.

It is not surprising that the California case law collections of several online services exhibit significant shortcomings.

IV. The Example Set by California’s Other Branches of Government

From the early days of the Internet, California has published its constitution and codes online – at a public site that allowed citizens, legal professionals, and businesses to search for pertinent provisions or retrieve sections to which they had been referred by others. Commercial publishers and non-profit groups have been free to download up-to-date digital copies for republication in print or electronic format. Through enactment of the Uniform Electronic Legal Material Act (UELMA), Cal. Gov’t Code §§ 10290-10300, the California Legislature has taken the further steps of designating the electronic version of that core component of state law “official” and providing for its online publication in an authenticated form.

Since 1998 California’s Office of Administrative Law has been under a mandate to “make available on the Internet, free of charge, the full text of the California Code of Regulations” along with “a list of, and a link to the full text of, each regulation filed with the Secretary of State.” Cal. Gov’t Code § 11344.

V. Models of Digital Case Law Publication upon which California Can Draw

Two decades ago the American Bar Association recommended that the nation’s courts adopt a public domain citation system “equally effective for printed case reports and for case reports electronically published on computer disks or network services.” It proceeded to lay out the key components of such a citation system, one that would not require waiting for a decision’s publication in a printed volume but would instead enable courts to attach all necessary citation information to decisions at the point of release. By the end of 2016 nearly a third of the states had adopted some variant of this approach. A fairly recent example is Illinois, a state in which the statutory framework for decision publication and the number of published decisions are quite similar to California’s. In 2011 the Illinois Supreme Court ended official print publication of that state’s appellate decisions. Simultaneously it designated the versions placed at the court web site “official” and adopted a system of non-print-dependent citation. Those electronic documents, like California’s statutes, are digitally authenticated. Arkansas, Nebraska, New Mexico, Ohio, and Oklahoma provide further examples on which California could draw.

VI. No Small Challenge, but Substantial Potential Gains

As is true in so many other sectors, the principal challenge for the Judicial Branch of going digital lies not in the technology. The website which now provides access to California “slip opinions” could be used, just as well, to offer their final official versions. Meeting concerns about data integrity by providing digital authentication should not be a significant problem as the sites of the State Legislature and Illinois reporter of decisions (along with those of several other state court systems) demonstrate.

The truly difficult task in converting to electronic publication is the redesign of an established workflow, staffing pattern, and contractual framework. The reporter’s office has a small workforce. Speeding up and altering the editorial process would not only have implications for its deployment. Very likely the change would also affect the appellate courts whose decisions feed into that office. Without question, it would require a quite different publication contract. Under the terms and conditions executed in 2010 the state receives books; the final digital files remain in the publisher’s possession and control, embedded in its online system.

Offsetting the inescapable burdens of reform are likely cost savings and public gains. Much of the effort of the reporter’s staff and contractor is no longer justified. In the current information environment, the production of copyrighted summaries, headnotes, and classification headings almost certainly falls in this category. So do the tables and indices created for each volume. The reporter’s addition of parallel case citations is another historic practice of dubious continuing value. No doubt there are more.

Long-term public benefits of a more far reaching kind argue for the change. State and local units of government are major purchasers of legal information. California has a system of county law libraries for the very purpose of supporting the legal research needs of public officials, the legal profession, and the general public. Recent initiatives of the judiciary, legal service organizations, and the bar to improve access to justice all depend ultimately on timely, accurate, and economic distribution of the state’s judicial precedent. Yet timeliness, accuracy, and economy are all compromised by a print-based contractual relationship that gives a single publisher direct access to post-release editorial revisions, sole responsibility for establishing how individual decisions will be cited, and the exclusive right to sell the official reports, in both print and electronic form.

Realizing the benefits of switching to official digital publication will require serious work. With the current contractual arrangements ending in June 2017, the time to begin that work is now.