On May 17, 2010, the U.S. Supreme Court decided United States v. Comstock, holding that Congress had power under the Necessary and Proper Clause of the U.S. Constitution to authorize civil commitment of a mentally ill, sexually dangerous federal prisoner beyond his release date. (18 U.S.C. § 4248). Three and a half years later, the Court communicated the Comstock decision’s citation pagination with the shipment of the “preliminary print” of Part 1 of volume 560 of the United States Reports. That paperbound publication was logged into the Cornell Law Library on January 3 of this year. (According to the Court’s web site the final bound volume shouldn’t be expected for another year.) United States v. Comstock, appears in that volume at page 126, allowing the full case finally to be cited: United States v. Comstock, 560 U.S. 126 (2010) and specific portions of the majority, concurring and dissenting opinions to be cited by means of official page numbers.

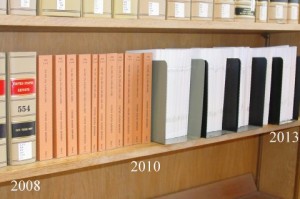

This lag between opinion release and attachment of official volume and page numbers along the slow march to a final bound volume has grown in recent years, most likely as a result of tighter budgets at the Court and the Government Printing Office. Less than two years separated the end of the Court’s term in 2001 and our library’s receipt of the bound volume containing its last decisions. By 2006, five years later, the gap had widened to a full three years. Volume 554 containing the last decisions from the term ending in 2008 didn’t arrive until July 9 of last year. That amounts to nearly five years of delay.

If the printed volumes of the Court’s decisions served solely an archival function, this increasingly tardy path to print would warrant little concern or comment. But because the Court provides no means other than volume and page numbers to cite its decisions and their constituent parts, the increasing delays cast a widening ripple of costs on the federal judiciary, the services that distribute case law, and the many who need to cite it.

The nature of those costs can be illustrated using the Comstock case itself.

The Need for Some Alternative Citation System to Use over the Lengthy Interim

As released the Court’s slip opinions do not provide the information necessary to meet current citation norms. For the period they carry Supreme Court decisions lacking official volume and page numbers legal database providers must, therefore, decide whether to employ a proprietary citation scheme of their own and further which of the dominant, competing unofficial volume and page number systems (S. Ct., L. Ed. 2d) to insert as slip opinion identifying numbers and divisions. Since neither of the latter are instantly available, their use requires later editorial intervention. None of these alternatives is without costs.

Incomplete and Temporary References in the Original Opinion Texts, Requiring Later Revision

In the original 2010 Comstock text (at page 20 of the slip opinion) Justice Breyer, writing for the majority, refers to a dissent by Justice Thomas, as follows:

Indeed even the dissent acknowledges that Congress has the implied power to criminalize any conduct that might interfere with the exercise of an enumerated power, and also the additional power to imprison people who violate those (inferentially authorized) laws, and the additional power to provide for the safe and reasonable management of those prisons, and the additional power to regulate the prisoners’ behavior even after their release. See post, at 12-13, 17, n. 11.

The Thomas dissent cites a 2008 decision of the Court but had to do so in the following form because it had not yet, in 2010, appeared with official report pagination:

To be sure, protecting society from violent sexual offenders is certainly an important end. Sexual abuse is a despicable act with untold consequences for the victim personally and society generally. See, e.g., Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U. S. ___, ___, n.2, (2008) (ALITO, J., dissenting) (slip op., at 9, n. 2, 22–23).

In the preliminary print volume Justice Breyer’s cross-reference reads: “See post, at 169, 170, 173-174, n. 12.” Note not only that it now lists three rather than two sets of pages but also that “n. 11” has become “n. 12”. Comparing the slip opinion and preliminary print, it seems evident the Court’s reporter of decisions was helped to see how, more precisely, the slip opinion page references mapped to the later version’s pagination and that the original footnote cross reference was off by one. (Although such changes have been known to occur, Justice Thomas did not add a footnote in the interim.) The citation in Justice Thomas’s dissent has been filled in and the parenthetical slip opinion references removed: “See, e.g., Kennedy v. Louisiana, 554 U. S. 407, 455, n.2, 468-469 (2008) (ALITO, J., dissenting).”

In short, because the Comstock decision, itself, and the Kennedy decision cited by Justice Thomas lacked permanent citation data in 2010, its text carried temporary and incomplete references that later had to be interpreted and filled in by the Court’s Reporter of Decisions (Frank D. Wagner through 2010, since 2011, Christine Luchok Fallon). That, however, is only the beginning of a cascade of revisions that must follow.

Database Services Must Detect, Extract, and Insert the Later Changes

All redistributors of the Court’s decisions must merge these and any other changes in the Comstock opinions into online versions that have been in place since spring 2010 – a costly process and one that injects risk of error. Strangely, the Court’s web site seems oblivious to the problem for it does not offer preliminary print versions of the United States Reports in electronic format. Consequently, legal database providers that care about conforming Supreme Court decisions to the official reports at this point must work from print. Their only alternative is to wait another year or so for release of the final bound edition which the Court does offer in digital format. (The most recent bound volume, received by the Cornell Law Library five years after the date of its contents, is the one holding the2008 Kennedy case cited by Justice Thomas. It is available for download at the Court web site.)

As of today, less than a month after the availability of Comstock in preliminary print form, what have the major online services done with its updated content?

Westlaw’s editors have inserted the official report page breaks in that service’s version of Comstock, but have failed to conform Justice Breyer’s cross reference. In Westlaw, as in the “Interim Edition” of the Supreme Court Reporter, his reference tracks the original, with the pagination converted to that in the company’s print reporter. It still points to “n. 11”. Justice Thomas’s citation to Kennedy v. Louisiana, has the jump cite pages in the official report blank, augmented by complete parallel references to the Supreme Court Reporter.

Lexis has caught the change in the footnote referenced by Breyer and substituted the official report pagination for that used in the slip opinion, placing the cross-reference pagination of its Lawyers’ Edition reporter in parallel. It has also filled in the blanks in Thomas’s citation of Kennedy, placing Lawyers’ Edition pages in parallel but it has missed the additional page range appearing in his citation that was not signaled in the original by a blank (“468-469”).

Bloomberg Law has inserted the official report page breaks but the cross reference remains exactly as it was in the slip opinion, complete with the now useless slip opinion pagination. The Thomas citation also stands exactly as it was, providing no page numbers in 554 U.S.

Loislaw has added the new official cite to the Comstock slip opinion, enabling retrieval by cite alone but has not added page breaks or conformed the text in other ways.

Casemaker has not added the official cite so the case must be retrieved by name or by use of the Supreme Court Reporter cite. The case carries Supreme Court Reporter page breaks and is in other respects conformed to the Thomson Reuters edition.

Fastcase holds the case in slip opinion form, with slip opinion pagination, but it can be retrieved using the Supreme Court Reporter cite.

Google Scholar like Casemaker conforms to the Supreme Court Reporter and does not yet reflect the availability of the official version or its cite.

The Multiplier Effect: Other Cases

This is only the beginning of the cascade, for during the three and a half years separating Comstock’s release and its acquiring an official cite the decision was cited (necessarily in some incomplete or unofficial fashion) by hundreds of lower courts. Shepards (Lexis) shows 191 entries on Comstock’s subsequent appellate history, 231 other citing decisions, and 441 citing references in law reviews and treatises. Legal database providers must decide which of these references to edit to include the Supreme Court’s decision’s official citation and how, if at all, to translate any pinpoint references into official pagination.

A Citation System that Avoids These Costs

How much simpler it would be for those of us who work with case law and less costly for the services on which we rely if the U.S. Supreme Court were to release its decisions in final and citable form rather than allowing a three to four year lag between release and the near final preliminary print.

Illinois appellate decisions (as well as those of several other states) demonstrate the comparative advantages of such an approach.

Less than a year ago, on March 21, 2013, the Illinois Supreme Court released People v. Cruz, 2013 IL 113399. One of several intermediate appellate court decisions to cite Cruz decided in the months immediately following was handed down only eight days later, People v. Cage, 2013 IL App (2d) 111264. Because Illinois decisions have, since 2011, been released with full official citation information the Cage references could be both complete and final:

¶ 15 We find support for our determination in our supreme court’s recent decision in People v. Cruz, 2013 IL 113399, 985 N.E.2d 1014, 369 Ill. Dec. 28. In Cruz, the defendant filed a petition seeking relief under the Act. The case proceeded to the second stage, and the State moved to dismiss, arguing, inter alia, untimeliness; the trial court granted the State’s dismissal motion. Id. ¶¶ 8, 15. The defendant appealed, and the State argued for the first time that the trial court’s dismissal should be affirmed because the defendant failed to attach a notarized affidavit to his pro se supplemental petition alleging a lack of culpable negligence. Id. ¶ 16. The appellate court agreed with the State, concluding that, “‘because [the defendant] filed no notarized affidavit to support the allegations of cause for the delayed filing, the trial court properly dismissed the postconviction petition.’ [Citation.]” Id.

Under the Illinois citation scheme, cross-references between opinions in a case can also be complete and in final form without a need to wait months or years to see what volume or page numbers have been assigned to the passages in question. Footnotes 1 and 2 in the majority opinion of Chicago Teachers Union v. Board of Education, 2012 IL 112566, illustrate:

1. The dissent appears to assign pretextual motives to the Board’s economic layoff of tenured teachers. Infra ¶ 41 (Theis, J., dissenting, joined by Kilbride, C.J.). However, it is undisputed that the layoffs in this case were based on nonpretextual economic reasons.

2. The dissent acknowledges this statutory distinction (infra ¶ 45 (Theis, J. dissenting, joined by Kilbride, C.J.)), yet fails to recognize its legal significance in construing these statutes.

Legal information providers can load Illinois decisions “as is”. When they later receive volume and page numbering in unofficial reports (notably N.E.2d of the Thomson Reuters National Reporter System) they can, but need not, merge the resulting case cites and page breaks into the official versions.

Conclusion

At a time when few researchers rely on print reports, the Supreme Court’s continued dependence on a set of print volumes, produced long after the fact, for a case’s official cite (and final text) is a costly anachronism. The growing lag in production of those volumes cannot be excused by the existence of many electronic sources. Indeed, their number and importance in legal research increase the ultimate burden of the delay.

Finally, there is an indeterminate hidden cost. So long as years separate initial slip opinions from their final official versions, justices face a troubling temptation to continue fiddling with their texts. One trusts that a desire to have a lengthy period for revision is not the cause of the recent increase in delay, but that delay does inevitably invite authorial “improvement”.