Shepard’s Citations

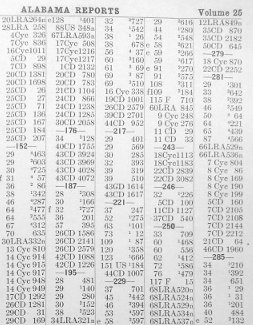

In 1873, Frank Shepard began compiling and selling lists of citations to Illinois decisions printed on gummed paper (Shepard’s System of Adhesive Citations). Purchasers pasted them into the margins of their bound case reports. Shepard’s lists linked each reported case to any subsequent reported decision that referred to it. When gummed addenda proved too cumbersome a tool (even more troublesome to maintain than looseleaf volumes), Shepard’s Citations moved to separate volumes. These were books of citations designed to stand beside law reports – volumes that simply pointed from one book to others by means of citation.

For over a century law students, lawyers, and judges conducted forward citation searches on key decisions using the Shepard’s publications. So tight was the association that the process became known as “Shepardizing”. One “Shepardized” a case to assure it had not be overruled by a higher court, to determine its status and range of interpretation within the jurisdiction of origin, to see how it had been treated elsewhere.

Cases and Citators Go Digital

Once electronic databases were central to case research, their incorporation of a citator function became essential. The value of providing the digital equivalent of Shepard’s gummed list proximate to every retrieved opinion was obvious. And in a hypertext environment that list of citing cases could itself offer point and click access to each one of them. Moreover, once held in a database the entries could be filtered and sorted. Today, all case law database services of professional quality offer retrieval of subsequent citing cases as an option adjacent to each opinion. Some not only list the citing cases but analyze and characterize those references as the Shepard’s print publications once did.

As electronic case law collections evolved, however, they posed fresh challenges for these companion citators. Increasingly the leading online databases added decisions that the Shepard’s lists had ignored, cases without standard print citations. These included opinions that would never be published in print, either because of court designation or publisher discretion, as well as “slip” versions of those whose publication was anticipated but had not yet occurred. Generally unexamined is the extent to which the relative performance of today’s online citators is affected by how they deal with citations in and citations to opinions falling in these two categories. That performance varies considerably. Researchers who assume complete results are, with some services, likely to miss important cases. Those who know the limitations of the citator on which they rely can, when necessary, augment its results with their own database search.

The Citator Challenges Posed by Unpublished Decisions

Citations to Not Yet Published Decisions

Because of their high volume Social Security cases provide a particularly clear illustration of the problem posed by the delayed application of citation parameters and the range of responses to it by the citators now embedded in the major online services. As of April 23 five “precedential” decisions in cases appealing a denial of benefits by the Social Security Administration had been released by the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals since the beginning of 2015. (Decisions the Court does not deem significant to other cases it labels “Nonprecedential” and withholds from publication in the Thomson Reuters Federal Reporter series.) “Four of the five were written by Judge Richard Posner. Three of his decisions and one by Judge Daniel Manion reversed trial court decisions that had affirmed the agency’s benefit denial.

From the moment of release, the potential ripple effect of opinions like these is substantial, throughout the district courts falling within the Seventh Circuit and beyond. Consider the numbers. During the twelve months ending June 30, 2014, those districts received 1,441 Social Security appeals. Within weeks, in some cases days, the five 2015 Court of Appeals decisions were being cited. Curvin v. Colvin, No. 13-3622 (7th Cir. Feb. 11, 2015), the earliest of the set, has now been cited at least 12 times. (A pro-claimant Social Security decision of the Seventh Circuit handed down a little over a year ago – Moore v. Colvin, 743 F.3d 1118 (7th Cir. 2014) – has been cited over 125 times, at least twice outside the circuit.)

Curvin illustrates the difficulty faced by anyone or any system attempting to track these citing references. The decision was handed down on February 11, 2015 but did not receive its “778 F.3d 645” designation until a month and a half later. During the intervening weeks it was cited at least eight times by district courts within the Seventh Circuit. Perforce those citations identified the Seventh Circuit opinion by docket number and exact date or a proprietary database citation (“WL”). Most, but not all, used both in parallel, yielding citations in the following form: Curvin v. Colvin, No. 13-3622, 2015 WL 542847 (7th Cir. Feb. 11, 2015). A straight database search on “778 F.3d 645” will not retrieve those cases. A database search on “2015 WL 542847” will retrieve those using the Westlaw cite (but not those employing the LEXIS equivalent “2015 U.S. App. LEXIS 2170” or the “F.3d” cite). A search on “13-3622” and “Curvin” will retrieve those including Curvin’s docket number but not those relying solely on a proprietary database cite or the ultimate “F.3d” cite.

Most case law databases purport to do this messy work for the researcher. With some Curvin’s rank in a set of search results may even be determined by how many citations to it there have been. What not all manage to do is to include those instances of citation that occurred so soon after Curvin’s release they could not refer to the case as “778 F.3d 645”. A review of how the major systems actually address this issue (or don’t) follows.

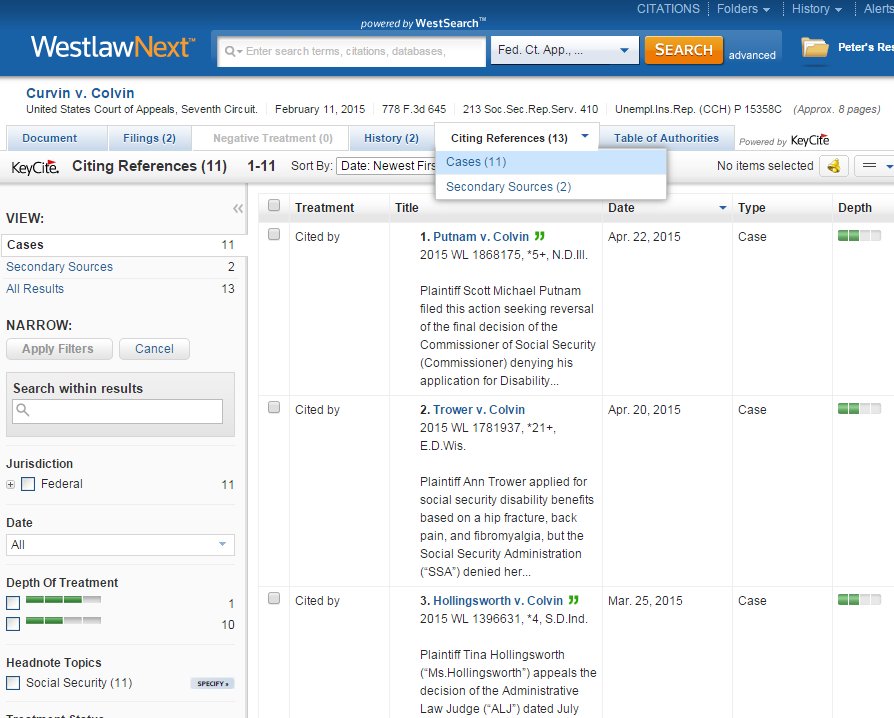

Westlaw

The dominance of Westlaw within the federal judiciary gives that system a clear advantage. So long as the early decisions cite the not-yet-published version of a case using its “WL” citation, Westlaw can employ that identifier to link them with those citing to the version later published in the company’s National Reporter System (NRS). But what about decisions written by federal judges who use LexisNexis and cite using its proprietary system? Senior Judge Donetta W. Ambrose of the Western District of Pennsylvania falls in this category. Had she relied on Curvin in late February or early March 2015, her opinion would almost certainly have cited it: Curvin v. Colvin, 2015 U.S. App. LEXIS 2170 (7th Cir. 2015). (See, for example, her decision in Nickens v. Colvin.) How would Westlaw have responded? It would have added a parallel “2015 WL 542847” to her Lexis cite, as it does to all opinion citations to “not yet published” or “never to be published” cases contained in the Westlaw database. That editorial step simplifies aggregation of all citations to a case prior its print publication. While Westlaw no longer displays the “WL” cite for decisions that have been given print citations in the National Reporter System, the service’s citation listings rest on its maintaining the association between preliminary “WL” cites and their subsequent NRS equivalents. This approach enables Westlaw’s listing of cases citing Curvin to include the early ones that did not use its F.3d volume and page number.

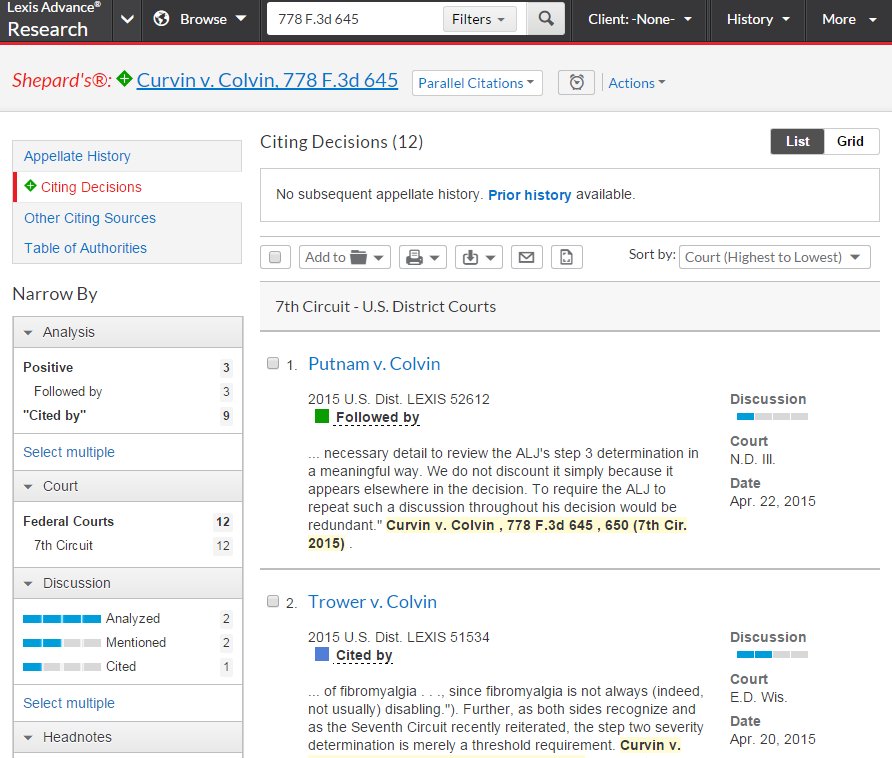

LexisNexis

Lexis follows a similar strategy. Since most federal judges use Westlaw most of the early decisions citing Curvin used its Westlaw cite. See, e.g., Haire v. Colvin, No. 1:14-CV-00322-TAB-JMS (S.D. Ind. Feb. 20, 2015). On Lexis the cite to Curvin in Haire includes an added “U.S. App. LEXIS” cite. That enables the inclusion of Haire in the service’s dynamically generated list of decisions citing Curvin. It also facilitates another Lexis practice, the subsequent addition of parallel “F.3d” cites to decisions that did not, as written, include them.

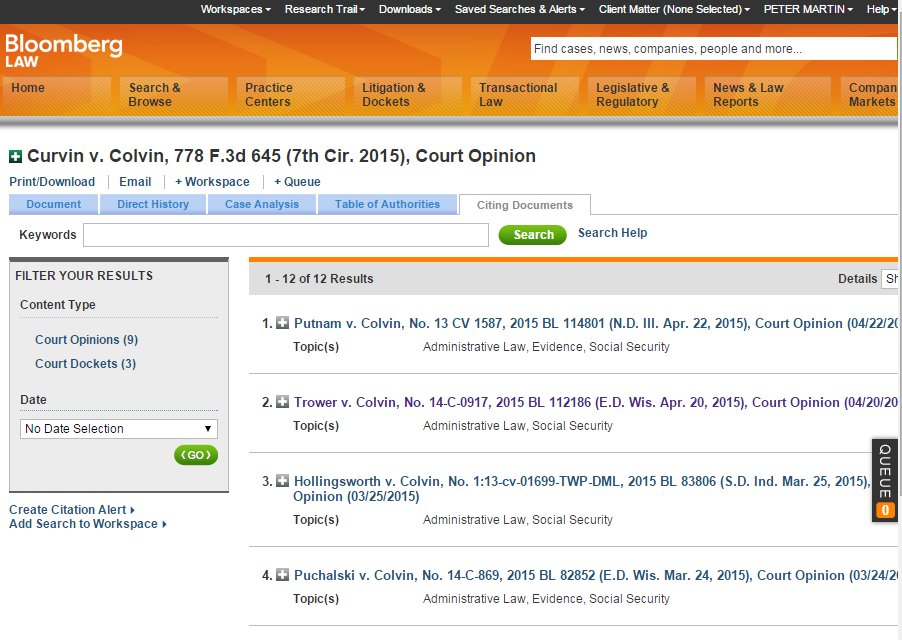

Bloomberg Law

Bloomberg has a “BL” citing scheme which it now deploys much like the Lexis cites, but with greater clarity. When a case in its database is cited by a later decision using only docket number and date or a Westlaw or Lexis cite, Bloomberg inserts a parallel “BL” cite. This editorial addition is, however, placed in square brackets, an acknowledgment that it was not part of the original text. Bloomberg Law has expanded Haire’s cite to Curvin written by the court as “Curvin v. Colvin, No. 13-3622, 2015 WL 542847, at *4, — F.3d —- (7th Cir. Feb. 11, 2015)” to “Curvin v. Colvin, No. 13-3622, [2015 BL 34654], 2015 U.S. App. LEXIS 2170 , 2015 WL 542847 , at *4, ___ F.3d ___ (7th Cir. Feb. 11, 2015)”. This practice appears relatively new. Decisions of an earlier vintage Bloomberg loaded as received without adding “BL” parallel cites. As a result decisions from that period are missed by Bloomberg’s linked retrieval of citing documents. (The fact that Bloomberg’s versions of decisions now also include the Lexis cite, without the square brackets, suggests a data sharing arrangement between the two companies.)

Judging at least from this sample of one, Bloomberg appears to add cases more rapidly than either Westlaw or Lexis. During the week of April 20th two more district court decisions citing Curvin were released. Both were in the Bloomberg database and listed as citing cases the following day.

The More Limited Approach of Google Scholar, Fastcase, and Casemaker

Google Scholar does not to attempt to track citing references for cases until they have received a permanent citation in the Thomson Reuters books. To date it does not have the NRS version of Curvin. When one clicks on the “How cited” link for the “slip” version of the case, one gets the message: “We could not determine how this case has been cited.” To find those cases a researcher must know to search on the party names and Curvin’s docket number or, alternatively, on its proprietary cites. The latter, of course, do not appear on Google Scholar or the public domain version of Curvin released by the Seventh Circuit and now (and forever?) available from the GPO’s Federal Digital System (FDsys). At some point Scholar will replace the original version of Curvin with that published by Thomson Reuters. Once it has, the decision’s “How cited” link will work, but it will not retrieve the early cases which did not cite Curvin by volume and page number because they could not. Researchers who know that can augment Google’s automatically generated list by doing the sort of searches suggested above.

Like Google Scholar both Casemaker and Fastcase limit their retrieval of citing cases to those that cite by means of NRS volume and page number, thereby missing the earliest references. Leavitt v. Cohen, No. 1:12-cv-1427-DKL-JMS (S.D. Ind. March 4, 2014) cited Moore v. Colvin, 743 F.3d 1118 (7th Cir. 2014), released less than a week before, using the format: Moore v. Colvin, ___ F.3d ___, 2014 WL 763223, *1(7th Cir. 2014). Since neither Fastcase nor Casemaker later fill in such blank “F.3d” citations or employ an enduring identifier for Moore (like the proprietary citation schemes of Bloomberg, Lexis, and Westlaw) neither includes Leavitt as a case citing Moore as those services do.

What about Newcomers like Ravel Law and Casetext?

Casetext does not yet have a fully developed method of indexing citing cases. It is designed to allow the ranking of search results by “Cite count” but while its database includes many more it lists only two cases as citing Moore.

Ravel has stronger incentive to solve the citator problem because its visualization of search results derives in significant part from citation links. However, to date Ravel’s cite count does not include case citations that pre-date the availability of the canonical NRS volume and page cite for a case. It counts only 70 cases as citing Moore v. Colvin. Those in its database not using that decision’s full “F.3d” cite do not make the list.

Citators and Never-to-be-Published Decisions

A 2013 “unpublished” Social Security decision of the Ninth Circuit illuminates this closely related citator issue. In Farias v. Colvin, No. 11-57088 (9th Cir. May 20, 2013), the court reversed a district court decision that had affirmed a denial of disability benefits. Its memorandum opinion faulted the Administrative Law Judge’s uncritical acceptance of testimony from a vocational expert. Being an unpublished memorandum opinion the Farias decision does not enjoy the status of precedent even within the courts that comprise the Ninth Circuit. Print-based Shepard’s would have ignored it.

On the other hand, unpublished decisions like Farias can be cited by counsel as persuasive authority. In fact, at least fifteen subsequent (unpublished) district court decisions refer to the Farias case. Because of the Thomson Reuters Federal Appendix reporter, Farias did in fact receive a print citation before 2013 was over, notwithstanding its “unpublished” designation, but not before being cited in at least two district court decisions. Thus, in one sense cases like it pose the same problem for citation compilers as those posed by cases eventually published in the Federal Reporter – a need to gather the earliest citations together with later ones expressed in terms of print volume and page numbers. However, the decision’s “unpublished” status and the dubious value of “Fed. Appx.” cites has led some case law services to stumble over providing useful citator results. The major three –Bloomberg, Lexis, and Westlaw – use their respective systems of proprietary citation to link Farias to the full spectrum of citing district court decisions. In contrast users of Google Scholar, Casemaker, and Fastcase are led to believe that Farias has not been cited unless they know enough to undertake a forward citation search on their own. And because some of the citing cases use the Farias decision’s “Fed. Appx.” cite and others don’t, some include the case docket number but most don’t, some use a proprietary database citation and others not, no single search other than one based simply on the case name (“Farias v. Colvin”) will retrieve them all.

One More Argument for Adoption of Court-Applied Systems of Citation

In jurisdictions that attach official citations to decisions at the time of release there is little difficulty generating a complete list of subsequent citing cases. Assuming that the court-attached citations are routinely used (whether or not in parallel with the National Reporter System or any other citation) a simple database search will retrieve all citing references. In 1999 the Oklahoma Supreme Court decided an influential case dealing with attorney malpractice liability. When released it carried the designation “1999 OK 79”. A search on that string, whether carried out directly by a researcher or automatically by software generating a citator list, should gather a comprehensive list of references to Manley v. Brown. That fact has enabled the Oklahoma State Courts Network database to append a list of citing cases to the decision in Manley. Although the case appears in the National Reporter System as “989 P.2d 448” a researcher or automated citator searching cases for references to Manley will not be thrown off by use of that print reference so long as it appears in parallel with the court-attached cite, as it does in all Oklahoma decisions and in a 2013 decision of the Illinois Appellate Court. Any citation search that relies solely on NRS citations for Oklahoma cases runs the risk of missing some.