I. C.F.R. Versus e-CFR and its Progeny?

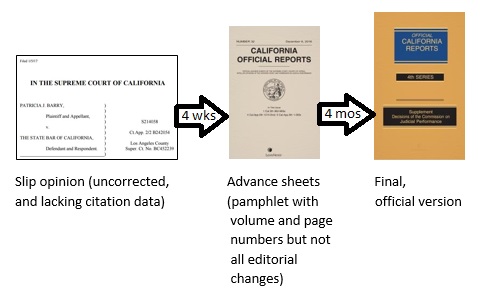

A. The Historic Print-Determined Timeline

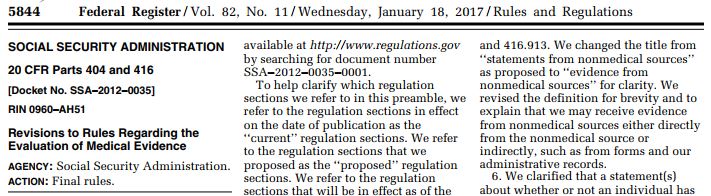

Federal regulations pose the same fundamental citation question as do provisions in the United States Code. On January 18, 2017, important new and amended regulations governing the determination of disability benefit claims under the Disability Insurance and Supplemental Security Income programs were published in the Federal Register.

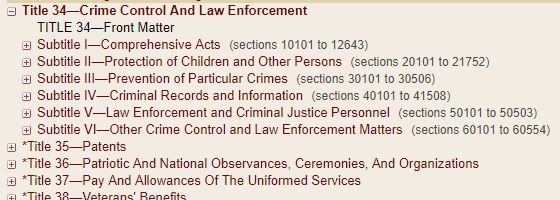

The changes took effect on March 27. The Federal Register for that very date contained a series of “technical amendments” cleaning up minor drafting errors in the January version of the text. Those corrections arrived just in time to beat the April 1st cutoff date for the volume of the 2017 print edition of the Code of Federal Regulations that contains Part 404 of Title 20. That is where the regulations governing these programs are organized. (The Code’s annual editions are published in four waves: “[T]itles 1-16 are revised as of January 1; titles 17-27 are revised as of April 1; titles 28-41 are revised as of July 1; and titles 42-50 are revised as of October 1.”)

In due course the volume containing all Social Security Administration regulations, as of April 1, 2017, was published by the Office of the Federal Register of the National Archives and Records Administration. In that physical form the new regulations, fully compiled and in context, made their way to Federal Depository Libraries, arriving in mid-September.

Date of Arrival: September 13, 2017

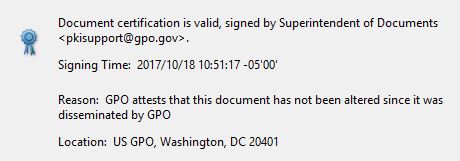

Following distribution of the printed volume, a digital replica in PDF was placed online as part of the Government Publishing Office’s Federal Digital System (FDsys).

The citation issue posed by that schedule is this: During the eight months that separated initial publication of these regulations from their appearance in a volume of the “official” Code of Federal Regulations (print and electronic) would it have been appropriate to cite them in accordance with the code location designations they carried from the moment of release? Take the revised 20 C.F.R. § 404.1521, for example. The pre-2017 version of that section dated from 1985. How should a legal memorandum written and filed in July 2017 have cited the text of the section by then in effect?

Citation norms, formed during the era in which the printed volumes of the Code of Federal Regulations and its companion, the Federal Register, were the only trustworthy means of accessing federal regulatory texts, would require citing such a recently revised provision to the Federal Register issue dated January 18, 2017, until the C.F.R. volume holding it could be inspected.

B. e-CFR and Derivative Compilations

Today the same public offices that publish the official Code of Federal Regulations also prepare and disseminate online a continuously updated version of the Code they call the “Electronic Code of Federal Regulations” or e-CFR. It lags the most recently published final regulations by a few days, at most.

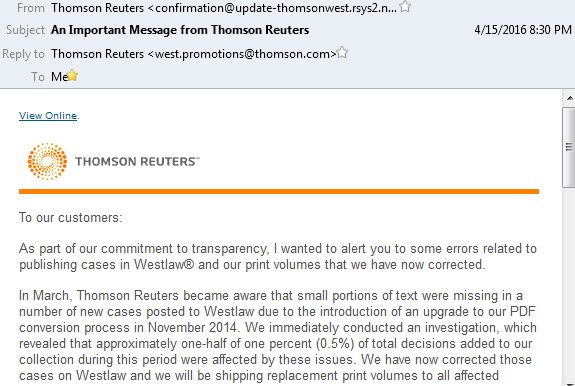

On December 8, for example, all sections of the e-CFR were current as of December 6. As is true with the Office of Law Revision Counsel’s online version of the United States Code, the e-CFR can be downloaded in bulk (in XML). That makes it possible for all major online legal information services to offer comparably up-to-date versions of the C.F.R. In short, in the current research environment, the lawyer, judge, or legal scholar who would read, quote, and cite to provisions of the Code of Federal Regulations as they stand at the moment of writing has no excuse not to draw upon the e-CFR or one of its reliable derivatives. (The latter include up-to-date versions of the C.F.R. maintained by Bloomberg Law, Lexis, Westlaw, and Cornell’s Legal Information Institute (LII).)

II. Chronological Version as Distinguished from Source

A. Disambiguating Recently Altered Provisions

Unless the citation to a compilation like the Code of Federal Regulations or the United States Code indicates otherwise, it will be understood as pointing to the cited portion as it stood at the time of writing. Recent regulatory (or statutory) changes to a provision are likely to require a parenthetical note to remove uncertainty about the reference. With a citation to 20 C.F.R. § 404.1521, for example, the reader will want to know whether the writer is invoking the section’s language before or after the 2017 revision. The writer may well also want to signal to the reader that she is aware of the change. On this score an initial citation reading “20 C.F.R. § 404.1521 (as amended in 2017)” or even “20 C.F.R. § 404.1521 (as amended, 82 Fed. Reg 5844, 5868 (Jan. 18, 2017))” is more useful than one that simply furnishes the year of the most recent official publication or the “as of” date of an unofficial version. On the other hand, a citation to 20 C.F.R. § 404.130, which was last amended in 1990, need carry no such baggage.

The existence of the chronological slices represented by the annual official versions does provide a ready means for citing to provisions as they once read. So long as the context makes it clear that the writer means to refer to the language of the section as it stood before the recent change, a citation reading “20 C.F.R. § 404.1521 (2016)” should suffice. But standing alone, one reading “20 C.F.R. § 404.1521 (prior to the Jan. 18, 2017 amendment)” provides a reader with more information. The GPO’s online archive of past C.F.R. editions, which reaches back to 1996, allows retrieval of no-longer-current regulatory texts on the basis of such references.

B. The Citation Manuals’ Requirement of a Date Element in All Cases

Rule 14.2(a) of The Bluebook calls for a C.F.R. citation to include the year of the cited section’s “most recent edition.” No exceptions. The mandate applies to a provision like 20 C.F.R. § 404.130 which has not been amended for over a quarter century. For a citation in a memorandum completed in July 2017, this rule would require “20 C.F.R. § 404.130 (2016)”. A few months later, that, again per The Bluebook, would become “20 C.F.R. § 404.130 (2017)”. The Indigo Book, being limited in purpose to prying the citation system codified in The Bluebook out of its proprietary wrapper, takes precisely the same position. The ALWD Guide to Legal Citation (6th ed.) goes a step further and addresses the likelihood that the writer has relied on an online compilation more up-to-date than the once-a-year official edition. Acknowledging the e-CFR, it provides in Rule 18.1(c), that if one is relying on its version of the C.F.R. the citation should “indicate the exact date (Month Day, Year) through which the provision is current, and append its URL after the publication parenthetical.” If the writer has, instead, referred to a commercial service’s compilation, ALWD calls for the citation to take the form: “27 C.F.R. § 72.21 (Westlaw through Sept. 29, 2016)”. (The section in its example was last amended in 1995.) In the ordinary case, both are unnecessary.

C. How Federal Judges (and Lawyers Appearing before them) Cite the C.F.R.

With the exception of opinions of the U.S. Supreme Court do which include the year of the current volume in initial citations to the Code of Federal Regulations, the decisions of most federal judges cite its provisions generically. That is, so long as they are referring is to the language of a C.F.R. section currently in effect, they cite it without any indication of date or online source. See, for example, the citations in: Gorman v. Berryhill, No. 3:16-CV-05113 (W.D. Mo., Nov. 30, 2017); Trevizo v. Berryhill, 862 F. 3d 987 (9th Cir. 2017); and Cazun v. Attorney Gen., 856 F.3d 249 (3d Cir. 2017). Briefs filed by the U.S. Justice Department take the same approach.

D. The Publication Lag and Hoped-For Useful Life of Journal Articles May Legitimately Call for The Bluebook‘s or ALWD Guide‘s Approach

Generally, months pass between an author’s completion of a journal article and its eventual publication. Moreover, since publication delays are common, the date carried by the journal issue in which the article appears may or may not correspond to the actual date of its distribution. Finally, against the odds, the author may imagine the piece being read with care for years into the future. Arguably, these factors argue for attachment of an explicit statement of the “current as of date” to all cited statutory and regulatory code sections. At minimum their inclusion reminds an unknown, and perhaps distant, reader to check on whether subsequent amendments may have altered the force of the writer’s analysis.

In contrast, legal briefs and judicial opinions carry explicit dates of filing. So long as there is no indication to the contrary, those reasonably anchor an assumption that all citations to codified statutes and regulations they contain refer to the provisions in effect on that date.