The Supreme Court – Opening a New Term in Serious Arrears

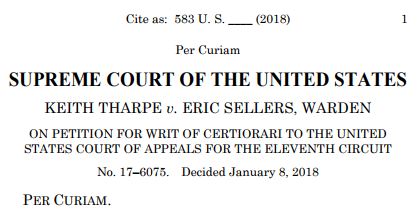

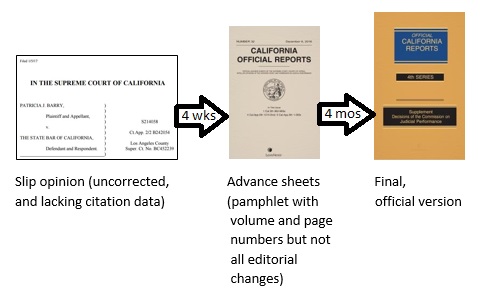

As the U.S. Supreme Court begins a fresh October term, the lag between its release of decisions and their publication, the topic of a previous post, has grown to embarrassing length. Today, decisions do not appear with their volume and page number assignments until four and one half to five years after they have been handed down. That critical information is provided to those who require it only when decisions are printed and distributed in a paperback “Preliminary Print” edition. The Preliminary Print covering the period Oct. 3, 2011 through January 17, 2012 (565 U.S. – Part 1) was published just this year and received by the Cornell Law Library on August 3, 2016.

Other courts, federal and state, obliged to follow Supreme Court precedent are left to cope with this immense citation gap. United States v. Jones, decided on January 23, 2012, held that installing a GPS device on a vehicle in order to track the vehicle’s movements constitutes a search under the Fourth Amendment. The case has, as of this date, been referred to in at least 998 subsequent judicial opinions. None has been able to cite the case or its key passages using the official, public domain format: “___ U.S. ___”.

What Can Others Do When the Lead Horse Is So Slow?

Adopt a Similar Pace

A few states that still publish print law reports are themselves years behind, although none so egregiously as the nation’s highest court. The most recent bound volume of the Nevada Reports concludes at the end of 2011. The volume and page numbers for individual decisions, assigned in preliminary prints, are, however, available up through May 2013.

When the Nevada Supreme Court cites decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court for which the official citation is available it uses only that, no parallel references. An August 2016 Nevada case, McNamara v. State, illustrates the court’s preferred format:

[W]e also reject McNamara’s argument that the failure to submit the question of territorial jurisdiction to the jury violated his Sixth Amendment rights as articulated in Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000).

The Supreme Court’s citation lag forces at least temporary use of an unofficial, commercial source and citation scheme. The author of a 2013 Nevada Supreme Court decision, Holmes v. State, relying on a U.S. Supreme Court’s decision of the year before, cited it as follows:

This argument fails under Howes v. Fields, 565 U.S. __, __, 132 S. Ct. 1181, 1192-94 (2012), because the interrogation was not custodial ….

Neither this Nevada decision nor the cited Supreme Court decision, Howes, is yet out in a preliminary print. There is no reason to imagine that Nevada’s publication delay has been induced by that in the nation’s capital. Yet because the two are both so far behind the Nevada Supreme Court staff will, in all likelihood, be able to fill in the skeletal U.S. Reports reference and drop the parallel Supreme Court Reporter cite when Holmes v. State is readied for final publication.

Ignore and Keep Moving

Most U.S. courts publish their precedent in final form with a degree of promptness that precludes citation of recent Supreme Court decisions to U.S. Reports. That is especially true of jurisdictions that have shifted from print to official digital publication. Illinois appellate decisions move from preliminary to final version quite swiftly. The average elapsed time is less than two months. Furthermore, from the moment of release any court, lawyer, or commentator can cite to an Illinois Supreme Court decision in official form. That is because, at release, each decision carries complete public domain citation information. Because of that jurisdiction’s commendable speed, any Illinois decision that includes a citation to or quotation from an opinion of the U.S. Supreme Court less than four years old cannot employ a full U.S. Reports citation. It must instead rely on a commercial service for the permanent effective reference, as in the following:

This court did not intend to overrule a significant body of case law by this single sentence. “We resist reading a single sentence unnecessary to the decision as having done so much work.” Arkansas Game & Fish Comm’n v. United States, 568 U.S. ___, ___, 133 S. Ct. 511, 520 (2012).

Richter v. Prairie Farms Dairy, Inc., 2016 IL 119518, ¶ 33.

New Mexico decisions face the same problem and adopt the same approach. See Morris v. Brandenburg, 2016-NMSC-027, ¶ 23. The Oklahoma Supreme Court doesn’t waste space with a skeletal “__ U.S. __, __”. See Okla. Coalition for Reproductive Justice v. Cline, 2016 OK 17, ¶ 3. That also holds for the print-published opinions of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. See Commonwealth v. Arzola, 470 Mass. 809, 818 (2015).

One Possible Solution for the Court: Take a (Virtual) Page from Nebraska’s Law Reports

Four years ago, confronted by publication delays comparable to those now afflicting the U.S. Reports, Nebraska’s Supreme Court established an Electronic Publications Committee. Its charge was to devise a plan for cutting loose from the costs and delays generated by publishing books that few wanted to buy. The scheme it developed was implemented as of the beginning of this year. By rule the Nebraska Supreme Court declared print publication of the Nebraska Reports and the Nebraska Appellate Reports complete, ending with volume 274 of the former (which contains 2008 decisions up through July 2) and volume 15 of the latter (cutoff date, October 8, 2007). Those volumes were, in fact, the most recently published at the time the committee began its work. Physical distribution of advance sheets ceased with the fulfillment of all outstanding subscriptions this June.

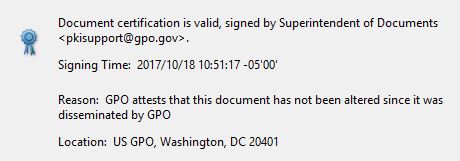

State administered case report publication continues in Nebraska but now solely in digital form. Liberated from the demands of print production, sale, and distribution, the Nebraska Reporter of Decisions, Peggy Polacek, and her staff have already chopped years off the state’s publishing backlog. Eleven virtual volumes of the Nebraska Reports and five of the Nebraska Appellate Reports were completed in final form over the summer. They reside, fully authenticated, within the Nebraska Appellate Courts Online Library site – an open repository of all published opinions of the Nebraska Supreme Court and Nebraska Court of Appeals.

Having years of decisions already in the publication pipeline, Nebraska opted not to alter the jurisdiction’s existing format or citation scheme. Decisions and their quoted or cited portions are still to be identified by volume and page numbers. Unlike other states that have taken their case law digital, Nebraska did not switch to medium-independent case designations or paragraph numbers. Nebraska’s continuing reliance on a print-oriented citation scheme does not mean that those relying on its precedent must await a decision’s being bundled with others for its citation information. From the moment of release, published Nebraska decisions carry their volume number and ultimate pagination. State v. Liner, released on September 13, 2016, is to be cited: “24 Neb. App. 311”. It runs through page 322 of volume 24. As was true when print was the official medium, content on page 318 of the “advance” version will remain on page 318 of the final “certified” electronic version. When the next Court of Appeals decision is published it will be “24 Neb. App. 323”. (The beginning of each decision starts a fresh page.) Every one thousand pages or so one digital volume is closed and the next, begun.

Could the U.S. Supreme Court Do the Same?

Unlike the “advance” opinions released by Nebraska’s appellate courts through its reporter’s office, the “slips” issued by the U.S. Supreme Court on the day of decision are not integrated compilations of the separate opinions they may contain preceded by the reporter’s syllabus. Each component, including that syllabus, has a full case heading. They may be stapled together in print and merged into a single electronic file, but syllabus, majority, concurring, and dissenting opinions are all paginated separately. Any cross-references they contain – majority opinion to dissent, for example – must take a temporary form that addresses that awkward fact. Would it add too much time to the pre-release work flow to have the reporter’s office pull these pieces together as Nebraska’s does, stripping off the separate headings, running consecutive pagination through all constituent opinions, and conforming the internal cross-references? It shouldn’t. That done, the only further step required to eliminate the present citation lag would be to assign cases to a volume and run their pagination in a continuous sequence rather than resetting each at “1”. In other words if the first decision of a term runs to eight pages, start the second at page “9”. If the second consists of a 4-page syllabus, 21-page majority opinion, and 21-page dissent, commence the third at page “55”, and so on. If all of this were to delay public release of the Court’s decisions a few days or even a week, the harm would be minimal, the gain, enormous. The reporter’s office already maintains consistent pagination between the preliminary print edition of a volume’s constituent parts and the ultimate bound versions. The Nebraska approach would simply entail moving that one stage earlier in the publication process.

Nothing in this set of editorial reforms would imply that the G.P.O. need cease printing volumes of the U.S. Reports. The principal aim would simply be to prevent the huge delays in print publication from denying timely access to official citation information. It is true that the very factors that drove Nebraska to designate the final electronic version of its published decisions “official” lie behind the tardy publication of the U.S. Reports. Budgets are tight, and the use of, and therefore demand for, print law reports has plummeted. It is quite possible that if Supreme Court decisions carried their official citation data from the moment of release and final electronic versions were certified weeks or months rather than years later, even greater delays in the production and distribution of bound volumes of those opinions might follow. But who would care? Today, nearly all case research is done online. In the present environment the timeliness with which authoritative, citable electronic versions of precedent are made available is vastly more important than rate at which those same opinions are physically archived in a set of books.

Dealing with the Deep Backlog of Skeletal Citations

Because of the size of the Court’s publication lag many of its own citations to prior decisions are temporary and incomplete. For example, in the last decision of the 2015 term, Voisine v. United States, the slip version of Justice Kagan’s majority opinion includes these case references:

- States v. Castleman, 572 U. S. ___, ___ (2014) (slip op., at 2) followed by numerous short form cites of the same case, many with slip opinion jump citations

- Armstrong v. United States, 572 U. S. ___ (2014)

- Descamps v. United States, 570 U. S. ___ (2013)

- Abramski v. United States, 573 U. S. ___, ___, n. 10 (2014) (slip op., at 18, n. 10)

Slotting Voisone into specific pages of a virtual volume 579 of the U.S. Reports or the first decision of this coming term into the beginning of volume 580 need not await completion of volumes 565 through 578. On other hand, because of the frequency of the Court’s self-citation, recent decisions cannot be put in final form without the reporter’s office working its way relentlessly forward through the existing backlog.

As noted above, once liberated from print production Nebraska’s reporter of decisions has been able to move through that state’s accumulated unpublished decisions with impressive speed. It should, perhaps, also be noted that while the U.S. Reports may be more years behind than were the Nebraska Reports when the Nebraska judiciary began work on that state’s electronic publication plan, measured in numbers of opinions the state’s challenge was greater. During the U.S. Supreme Court’s past term it rendered only 81 decisions of which 17 were per curiam, five of them one-liners. During calendar 2015 Nebraska’s appellate courts delivered 260 decisions to the state’s reporter of decisions for publication.

A Need to Take Electronic Publication More Seriously

Bound volume 563 of the U.S. Reports, running through June 6, 2011, has, since late June, been on a shelf in the Cornell Law Library. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court’s web site has not pushed past volume 561 (covering the end of the 2009 term). Undoubtedly, the two missing pdf files are held at the Court somewhere; they were prepared there. But which office has the responsibility for placing them online? Apparently, none has ever been charged with providing electronic access to the preliminary print versions of decisions, which in the current pattern of dissemination are the first to provide full citation information.

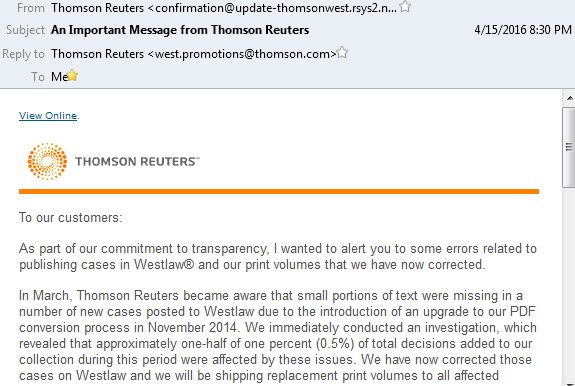

One development of the last term provides modest grounds for optimism. Having been called out in 2014 for the undisclosed post-release substitution of revised slip opinions, the Court’s web site has begun to note when such changes have occurred and to provide a means for determining the exact nature of the revision.

In today’s environment, reducing the time involved in bringing the Court’s decisions to print, whether preliminary or final, is no longer an important goal. Making them promptly available to the public, the legal profession, and the nation’s other courts in final citable form is and that requires a serious program of electronic publication.

Would Congressional Action Be Required?

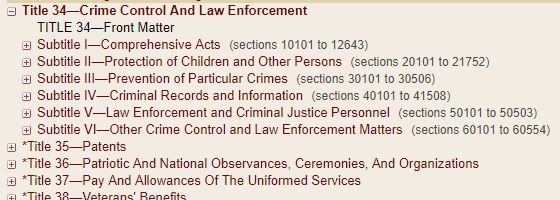

Most of the steps outlined here could be taken by Supreme Court staff without legislation. Following Nebraska’s lead all the way to cessation of print law report publication would, however, require that Congress amend the U.S. Code to authorize electronic publication as an alternative to print rather than a faster complementary track. Last year the Nebraska legislature passed such a bill, prepared by the state’s judicial branch.

For now 28 U.S.C. § 411 requires that: “The decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States … be printed, bound, and distributed in the preliminary prints and bound volumes of the United States Reports as soon as practicable after rendition ….” In recent years the “as soon as practicable” proviso has effectively swallowed the mandate of prompt printing and distribution. Ironically, in light of present realities, the act of 1817, which first established the reporter position, required publication of the Court’s decisions “within six months of their rendering.” Fifty years ago, when judges and lawyers still looked cases up in books, bound volumes of the U.S. Reports appeared within a year of the last decision they contained.

The time is ripe for the U.S. Supreme Court (indeed, for the full federal judiciary) to devote serious attention to the altered landscape of case reporting.