A. Background: How legislatures and agencies handle revision

1. Revision by Congress

When Congress enacts and the President signs a carelessly drafted piece of legislation it becomes the law. All must live with, puzzle over, and, in some cases, find an ad hoc way to cite what Congress has done. Congress can clarify the situation or correct the error but only by employing the same formal process to amend that it previously used to enact. In October 1998, Congress passed two separate bills adding provisions to Title 17 of the U.S. Code, the Copyright Act. Both added a new section 512. Embarrassing? Perhaps. Did this pose a serious question of Congressional intent? No. Clearly, the second new 512 was not meant to overwrite the first; the two addressed very different topics. Did this pose a problem for those who wanted to cite either of the new sections? For sure, but one readily addressed either by appending a parenthetical to disambiguate a reference to 17 U.S.C. § 512 or by citing to the session law containing the pertinent 512. In time the error was resolved by a law making “technical corrections” to the Copyright Act. One of the two sections 512 was renumbered 513.

During 2013 Congress passed four pieces of legislation that made “technical corrections” to scattered provisions of the U.S. Code. Unsurprisingly, tidying up drafting errors of this sort is not a high Congressional priority. For ten years there have been two slightly different versions of 5 U.S.C. § 3598; for nearly eighteen, two completely different versions of 28 U.S.C. § 1932. The Code contains cross-references to non-existent provisions and myriad other typos. Some are humorous (as, for example, the definition of “nongovernmental entities” that includes “organizations that provide products and services associated with … satellite imagines”). The various compilers of Congress’s work product do their best to note such glitches where they exist and, if possible, suggest that body’s probable intention. They do not, however, view themselves as at liberty to make editorial corrections.

2. Agency typos and omissions

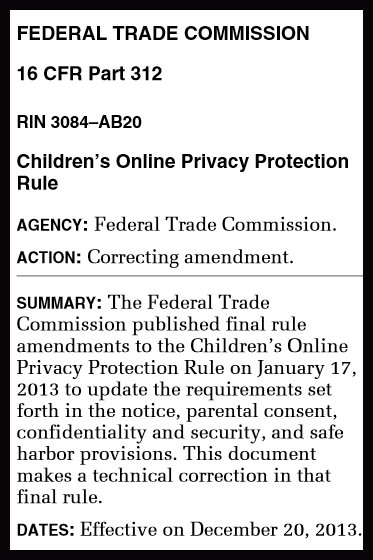

Pretty much the same holds for regulations adopted by federal administrative agencies. When a final regulation contains inept language, a typo, or some other drafting error, the Office of the Federal Register publishes it “as is”. The authoring agency must subsequently correct or otherwise revise by publishing an amendment, also in the Federal Register. Until the problem is caught and addressed through a formal amendment, the original version is “the law.” In the meantime, all who must understand or apply it – agency personnel, the public, and courts – must interpret the puzzling language in light of the agency’s most likely intent. The Federal Register is filled with regulatory filings making “correcting amendments.” A search on that phrase limited to 2013 retrieves a total of eighty. For a pair of straightforward examples see 78 Fed. Reg. 76,986 (2013).

B. Judicial opinions – An altogether different story

With judicial opinions the situation is startlingly different. When judges release decisions containing similar bits of sloppiness, the process for correcting them is far less certain and, with some courts, far less transparent. What sets courts apart from other law enunciating bodies in the U.S. is their widespread practice of unannounced and unspecified revision well after the legal proceeding resulting in a decision binding on the parties has concluded. Several factors, some rooted in print era realities, are to blame.

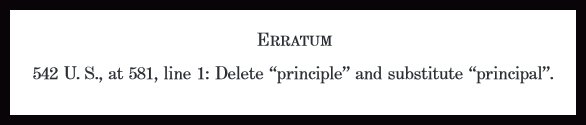

To begin, most U.S. appellate courts began the last century with the functions of opinion writing and law reporting in separate hands. Public officials, commonly called “reporters of decisions” cumulated the opinions issued by appellate courts and periodically published them in volumes, together with indices, annotations, and other editorial enhancements. Invariably, they engaged in copy editing and cite checking decision texts, as well, subject to such oversight as the judges cared to exercise. The existence of that separate office together with the long period stretching from opinion release to final publication in a bound volume induced judges to think of the opinions they filed in cases, distributed to the parties and interested others in “slip opinion” form, as drafts which they could still “correct” or otherwise improve. That mindset combined with the discursive nature of judicial texts, their attribution to individual authors, and judicial egos can produce a troubling and truly unnecessary level of post-release revision. At the extreme, judicial fiddling with the language of opinions doesn’t even end with print publication. Dissenting in Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004), Justice Thomas wrote: “The principle ‘ingredient’ for ‘energy in the executive’ is ‘unity.’” (The quoted fragments are from No. 70 of the Federalist Papers.) That was June 2004. The sentence remained in that form in the preliminary print issued the following year and the final bound volume which appeared in 2006. Volume 550 of the United States Reports published in 2010, however, contains an “erratum” notice that directs a change in that line of Thomas’s dissent, namely the substitution of “principal” for “principle.” Six years after the opinion was handed down, it is hard to understand who is to make that change and why — beyond salving the embarrassment of the author. None of the online services have altered the opinion.

Judges, even those on the highest courts, make minor errors all the time. What they seem to have great difficulty doing is letting them lie. This seems particularly true of courts for which print still serves as the medium for final and official publication. The Kansas Judicial Branch web site explains about the only version of opinions it furnishes the public:

Slip opinions are subject to motions for rehearing and petitions for review prior to issuance of the mandate. Before citing a slip opinion, determine that the opinion has become final. Slip opinions also are subject to modification orders and editorial corrections prior to publication in the official reporters. Consult the bound volumes of Kansas Reports and Kansas Court of Appeals Reports for the final, official texts of the opinions of the Kansas Supreme Court and the Kansas Court of Appeals. Attorneys are requested to call prompt attention to typographical or other formal errors; please notify Richard Ross, Reporter of Decisions ….

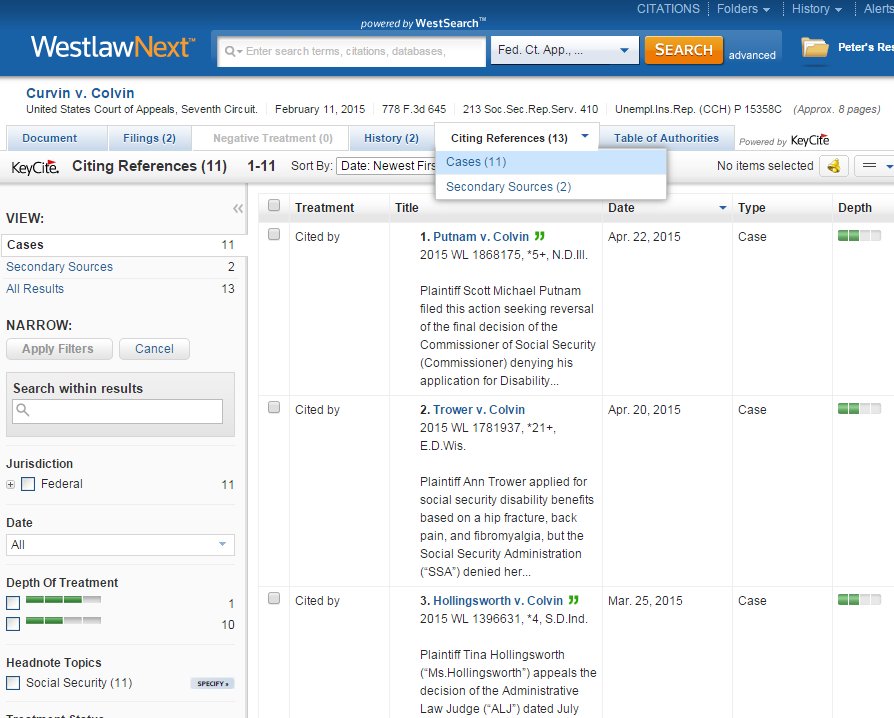

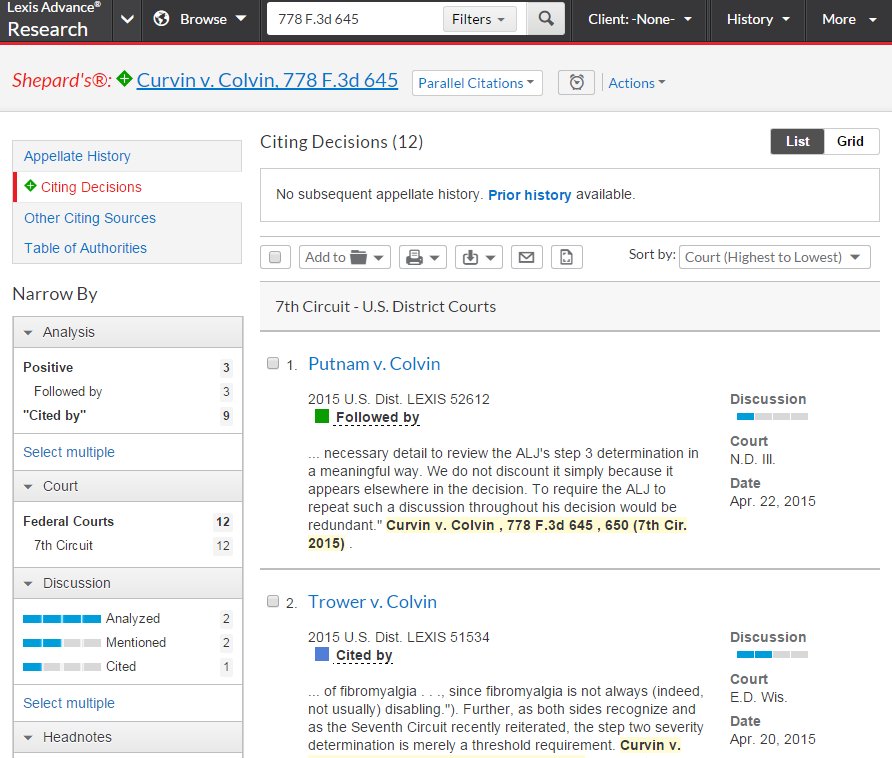

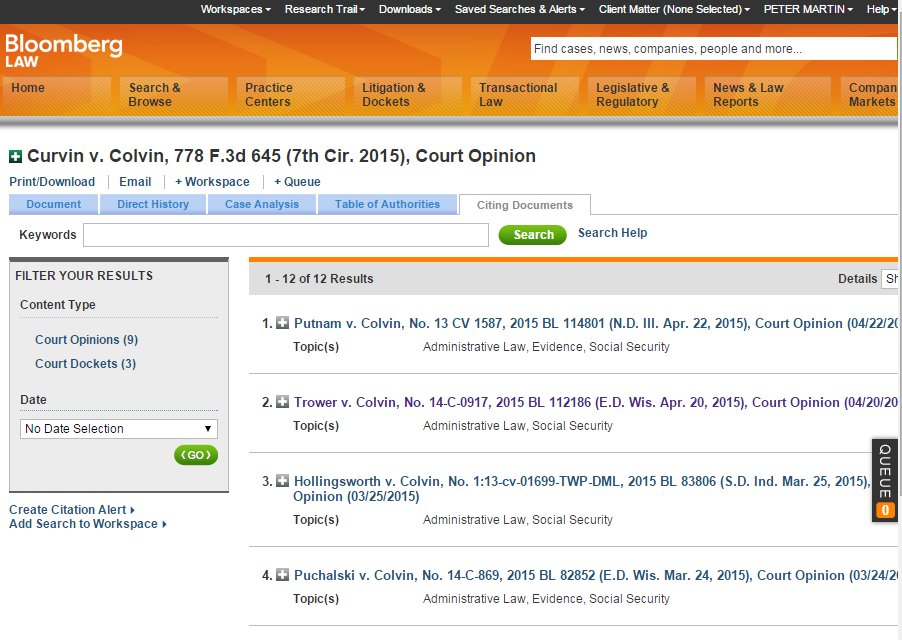

Since the path from slip opinion to final bound volume can stretch out for months, if not years, the opportunity for revision is prolonged. Moreover, unless the court releases a conformed electronic copy of that print volume, changes, large or small, are hard to detect. Interim versions, print or electronic, only compound the difficulty. For those who maintain case law databases and their users this can be a serious problem, one some of them finesse by not bothering to attempt to detect and make changes reflected in post-release versions.

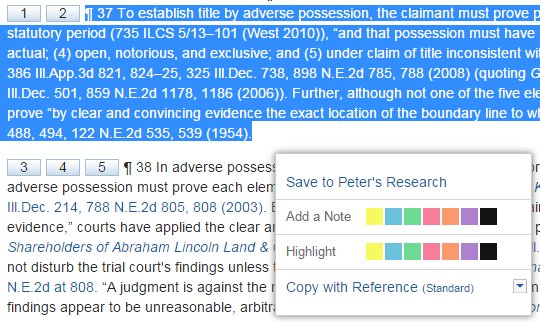

A shift to official electronic publication inescapably reduces the period for post-release revision since decisions need no longer be held for the accumulation of a full volume before final issuance. On the other hand, staffing and work flow patterns established during the print era can make it difficult to shift full editorial review, including cite, and quote checking to the period before a decision’s initial release. Difficult, but not impossible – the Illinois Reporter of Decisions, Brian Ervin, who retired earlier this year, appears to have achieved that goal when the state ceased publishing print law reports in 2011. Reviewing the Illinois Supreme Court’s decisions of the past year using the CourtListener site in the manner described below, reveals not a single instance of post-release revision.

Procedures in some other states that have made the same shift specify a short period for possible revision, following which decisions become final. Decisions of the Oklahoma Supreme Court, for example, are not final until the chief justice has issued a mandate in the case and that does not occur until the period for a rehearing request has passed. Decisions are posted to the Oklahoma State Court Network immediately upon filing, but they carry the notice: “THIS OPINION HAS NOT BEEN RELEASED FOR PUBLICATION. UNTIL RELEASED, IT IS SUBJECT TO REVISION OR WITHDRAWAL.” Once the mandate has issued, a matter of weeks not months, that warning is removed and the final, official version is marked with the court’s seal. In New Mexico, another state in which official versions of appellate decisions are now digital, a similar short period for revision is embedded in court practice. Decisions are initially released in “slip opinion” form. “Once an opinion is selected for publication by the Court, it is assigned a vendor-neutral citation by the Chief Clerk …. [During the interim the] New Mexico Compilation Commission provides editorial services such as proofreading, applying court-approved corrections and topic indices.” As a result of that editorial process, most decisions receive minor revision. For a representative example, see this comparison of the slip and final versions of a recent decision of the New Mexico Supreme Court (separated in time by less than a month). Once a decision can be cited, it is in final form.

Typically, when legislatures and administrative agencies make revisions the changes are explicitly delineated. Most often they are expressed in a form directing the addition, deletion, or substitution of specified words to, from, or within the original text. Except in the case of post-publication errata notices, that is not the judicial norm. Even courts that are good about publicly releasing their revised decisions and designating them as “substitute”,” changed”, or “revised” (as many don’t) rarely indicate the nature or importance of the change. So long as all versions are available in electronic form, however, the changes can be determined through a computer comparison of the document files. Such a comparison of the final bound version of Davis v. Federal Election Commission, 554 U.S. 724 (2008) with the slip version, for example, reveals that at page 735 the latter had erroneously referred to a “2004 Washington primary.” The later version corrects that to “2004 Wisconsin primary” – simple error correction rather than significant change.

More disturbing, by far, are:

- the common failure to provide the same degree of public access to revised versions of decisions as to the versions originally filed, and

- the substitution of revised versions of decisions for those originally filed without flagging the switch.

Any jurisdiction which, like Kansas, still directs the public and legal profession to print for the final text of an opinion without making available a complete digital replica is guilty of the first. Less obviously this is true of courts which, like the U.S. Court of Appeals, leave distribution of their final, edited opinions to the commercial sector. Less conspicuous and, therefore, even more troubling are revisions that courts implement by substituting one digital file for another before final publication. A prior post noted one example of this form of slight-of-hand at the web site of the Indiana Judicial Branch. But the Indiana Supreme Court hardly stands alone. Thanks to the meticulous record-keeping of the CourtListener online database such substitutions can be detected.

Like other case law harvesters, CourtListener regularly and systematically examines court web sites for new decision files. Unlike others it calculates and displays digital fingerprints for the files it downloads and stores the original copies for public access. When a fresh version of a previously downloaded file is substituted at the court’s site, its fingerprint reveals whether the content is at all different. If the fingerprint is not the same, CourtListener downloads and stores the second file. Importantly, it retains the earlier version as well. Consequently, a CourtListener retrieval of all decisions from a court, arrayed by filing date, will show revisions by substitution as multiple entries for a single case. Applied to the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court during calendar 2011 this technique uncovers ten instances of covert revision. Happily, none involved major changes. The spelling of “Pittsburg, California” was corrected in a majority opinion by Justice Scalia, “petitioner” was changed to “respondent” in a majority opinion by Justice Kennedy, “polite remainder” in a Scalia dissent became “polite reminder”, and so on. The perpetually troublesome “principal/principle” pair was switched in a dissent by Justice Breyer.

Most post-release opinion revisions involve no more than the correction of citations and typos like these, but the lack of transparency or any clear process permits more. And history furnishes some disturbing examples of that opportunity being exploited. Judge Douglas Woodlock describes one involving the late Chief Justice Warren Berger in a recent issue of Green Bag. Far more recent history includes the removal of a lengthy footnote from the majority opinion in Skilling v. United States, 561 U.S. 358 (2010). The slip opinion file now at the Court’s web site carries no notice of the revision beyond the indication in the “properties” field that it was modified over two weeks after the opinion’s filing date. To see the original footnote 31 one must go to the CourtListener site or a collection like that of Cornell’s LII built on the assumption that a slip opinion distributed by the Court on day of decision will not be changed prior to its appearance in a preliminary print.

C. Some unsolicited advice directed at public officials who bear responsibility for disseminating case law (reporters, clerks, judges)

1. Minimize or eliminate post-release revision

In this era of immediate electronic access and widespread redistribution, courts should strive to shift all editorial review to the period before release, as Illinois has done. Judges need to learn to live with their minor drafting errors. Finally, whatever revision occurs prior to final publication, none should occur thereafter. In the present age issuance of errata notices years after publication is a pointless gesture.

2. If decisions are released in both preliminary and final versions, make them equally accessible

While the final versions of U.S. Supreme Court decisions are much too slow in appearing, when they do appear they are released in both print and a conformed electronic file. Most U.S. courts are like those of Kansas and fail to release the final versions of their decisions electronically. Furthermore, some that do, California being an example, release them in a form and subject to licensing terms that severely limit their usefulness to individual legal professionals and online database providers.

3. Label all decision revisions, as such, and if the revision is ad hoc rather than the result of a systematic editorial process, explain the nature of the change

At least twice this year the Indiana Supreme Court released opinions that omitted the name of one of the attorneys. As soon as the omission was pointed out, it promptly issued “corrected” versions. In one case (but not the other) the revision bears the notation that it is a corrected file, with a date. In neither case is the nature of or reason for the change explained within the second version. As noted above, too many courts, including the nation’s highest, make stealth revisions, substituting one opinion text for a prior one without even signaling the change.

4. If revision goes beyond simple error correction, vacate the prior decision and issue a new one (following whatever procedure that requires)

United States v. Hayes, No. 09-12024 (11th Cir. Dec. 16, 2010), discussed in a prior post, provides a useful illustration of this commendable practice. United States v. Burrage, No. 11-3602 (8th Cir. Apr. 4, 2014), falls short, for while it explicitly vacates the same panel’s decision of a month before, it fails to explain the basis for the substitution.