A. Introduction

In a prior post I explored how the transformation of case law to linked electronic data undercut Brian Garner’s longstanding argument that judges should place their citations in footnotes. As that post promised, I’ll now turn to Garner’s position as it applies to writing that lawyers prepare for judicial readers.

Implicitly, Garner’s position assumes a printed page, with footnote calls embedded in the text and the related notes placed at the bottom. In print that entirety is visible at once. The eyes must move, but both call and footnote remain within a single field of vision. Secondly, when the citation sits inert on a printed page and the cited source is online, the decision to inspect that source and when to do so is inevitably influenced by the significant discontinuity that transaction will entail. In print, citation placement contributes little to that discontinuity. The situation is altered – significantly, it seems to me – when a brief or memorandum is submitted electronically and will most likely be read from a screen. In 2014 that is the case with a great deal of litigation.

B. Electronic briefs and memoranda filed with federal courts

Except for the Supreme Court, electronic filing is available in nearly all federal courts and proceedings. In many it is mandatory. With some federal courts that has been true for years. The recent advent of the iPad and follow-on tablets has allowed judges and their law clerks to place electronically filed case documents on the screen of a highly portable computer, one that is capable of accessing the full case record and the online legal research services used by the court with minimal interruption. A internal survey conducted by Federal Judicial Center in early 2012 found that fifty-eight percent of the judges in federal appellate, district and bankruptcy courts used an iPad for court work.

Inexorably that has led some judges to press for links between the citations in the documents they read from the screen and the authorities or portions of the record to which they refer. Local rules commonly permit their inclusion. Local Rule 25.1(i) of the Second Circuit is typical. It provides:

(i) Hyperlinks. A document filed under this rule may contain hyperlinks to (i) other portions of the same document or to other documents filed on appeal; (ii) documents filed in the lower court or agency from which the record on appeal is generated; and (iii) statutes, rules, regulations, and opinions. A hyperlink to a cited authority does not replace standard citation format.

An ad hoc group of federal judges and judicial staff has taken the further step of affirmatively encouraging such links.

The judges of the Fifth Circuit, not content to leave the matter to attorney initiative, prevailed upon the chief of the court’s technology division, Ken Russo, to develop an application that converts citations in e-filed briefs to links. In the case of citations to the record, the links retrieve the cited portion from the CM/ECF system. Citations of authority are linked to the online service of the reader’s choice (which during a period of transition between “classic” and next generation systems at both Westlaw and Lexis may well be different for judges and law clerks). Since the brief author or opposing counsel may be an attorney who uses Fastcase or Casemaker (both of which are represented in the states which comprise the Fifth Circuit) Russo’s system also contemplates those services as link options. To facilitate the programmatic linking of references to the record, the court issued a local rule, effective December 1, 2013, prescribing a new and distinctive format for such citations. Finally, anticipating similar link-related format changes in the future, the circuit has issued a rule 25.2.15 authorizing the clerk to “make changes to the standards for electronic filing to adapt to changes in technology.”

C. E-filing in Texas and other states

Electronic filing has progressed more slowly and unevenly in state courts. Nonetheless, it has a presence in most states, with mandatory e-filing existing to some degree in nearly half. Leading the pack, especially at the appellate level, is Texas. (Appellate e-filing in other states is summarized in a recent survey conducted by Blake Hawthorne, Clerk of the Texas Supreme Court.) On January 1, 2014, electronic filing became mandatory for cases in the Texas Supreme Court and for civil cases in the state’s intermediate courts of appeals. Like other appellate rules, federal and state, those in Texas had already been adjusted to the modern era by the conversion of document length limits from pages to maximum word counts. Because these are documents Texas judges read from screens of various sizes the minimum font size was, at the same time, increased from 12 point to 14. (All justices of the Texas Supreme Court have tablets and smart phones.) To ease the transition, court staff prepared detailed guidance on how to prepare briefs that not only comply with the new rules but are optimized to fit judicial work patterns and preferences. One guide includes advice on such points as how to structure a pdf document so as to facilitate the reader’s navigation through it, why and how to link to cited authority, and how to set the document’s original display in view of the writer’s uncertainty about the screen real estate it will occupy.

D. The implications for citation placement

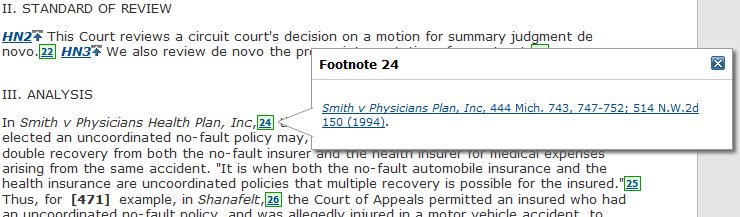

As noted in the prior post, today’s online legal research environment has replaced the judicial opinion “page” as the unit of view with the continuously scrollable document. Page break locations necessary for pinpoint citation are indicated, but there being no true page, footnotes are either moved to the document’s end or displayed in close proximity to their calls. The dominance of pdf as the format for e-filed documents might encourage the impression that, by contrast, the page remains a meaningful unit in the electronic brief. But whenever the reader may be working from a screen rather than a print copy of the file that impression is deceptive. In varying degrees, desktop, laptop, tablet, and smart phone all place the reader in control over how a pdf file is displayed. Depending on the device and application, readers may be able to open bookmarks allowing navigation within a document, immediately adjacent to its text. By zooming, they can increase the perceived size of the font at the expense of the amount of text they see on the screen. They can choose to scroll rather than page through a document. Footnotes remain footnotes, but on the screen there is a strong probability they will not be visible at the same time as the segment of the text to which they relate.

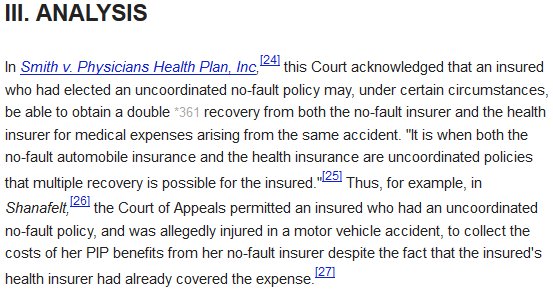

If the electronic document has been prepared with care, its footnote calls will be linked to the notes, and if citations have been linked to the cited authorities either by the author or, as in the Fifth Circuit, by court software, the path to those authorities will not depend on the citations’ sharing the reader’s field of vision with the propositions they support. On the other hand, the reader’s decision over whether and when to inspect a cited source now involves greater discontinuity than simple eye movement.

I will concede, as Garner stresses, that embedded citations inescapably interrupt the flow of the writer’s exposition, but use of that format is the only way, in an electronically filed brief, to assure that one’s citations are seen together with the textual material to which they relate. To the extent that a citation operates purely as a reminder to a judicial reader that proximity is useful. More importantly, however, if the judge or law clerk need simply touch or click the citation to view the authority or portion of the record to which it points, proximity at once informs and invites that move. That should be a move that a brief’s author will want to facilitate. For while judges write their decisions with authority and cite primarily to explain, lawyers write memoranda and briefs to persuade and cite to invoke the authority of others.

In sum, as more and more judges read lawyer submissions from a screen, with the near instant capability to follow citations to the case, statute, or record excerpt to which they refer, those who previously placed citations in footnotes have strong reason to reconsider.

E. Judge for yourself

The briefs filed with the Texas Supreme Court are available for inspection at a public web site. By court mandate they are filed in pdf. As the result of court encouragement many contain citations that can be executed by touch or click. Court staff tell me that the shift to electronic media has led to fewer briefs with their citations in footnotes. That pattern has not vanished, however. As a result, the court’s site contains examples of the alternative styles that anyone can examine and compare. I invite you to conduct the following experiment:

Download the following two briefs and work your way through them as though you were a judge. While doing so, consider these questions, bearing in mind the extent to which your answers are affected by the device and software you are using and the preferences you have set:

- Can one see the citation and the text it supports at the same time or does that require a scroll, click, or touch?

- If and when one chooses to follow the linked citation to the referenced source (and back) to what degree is that move facilitated or rendered more awkward by the citation’s placement?

From a current, high profile case:

F. Deeper issues raised by citations that are links

Citation placement is by no means the only or even the most important issue raised by the conversion of citations in briefs into executable pathways leading directly to the cited text or document. That larger topic will be the subject of a later post.